My brother Alan and I had the exciting experience last autumn of diving in the St Lawrence River on a submerged canal lock dating from the 19th century. What had once been an extensive canal system, built to allow ships to pass between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes, now lies deep beneath the floodwaters of a hydroelectric dam. As Alan’s film shows, the lock that we explored – Lock 21 of the Cornwall Canal – was a gloomy, forbidding place, swept by strong currents that made it a challenge to dive. Nevertheless, discovering the lock was highly rewarding and gave us an insight into a remarkable achievement of Victorian engineering, one that helped to shape Canada’s early history.

This map of the 1950s St Lawrence Seaway project illustrates the impact that improved navigation along the river was expected to have, allowing direct transport for large ships between the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. The original Cornwall Canal lies in the middle of the Seaway, mid-way between Montreal and Kingston.

On that same trip we filmed another amazing site near the entrance to the St Lawrence River on Lake Ontario, the wreck of the War of 1812 frigate HMS Prince Regent. The story of that ship and the other large warships built at Kingston in 1813-14 is intimately linked with the development of the canal. The British needed large warships on Lake Ontario to counter the American threat, with frigates and ships-of-the-line on the stocks at the US Navy yard at Sackets Harbour. But there was no way of bringing large warships up the St Lawrence from the Atlantic – there were too many areas of treacherous shallows on the river, including the Long Sault rapids near the town of Cornwall. The only option was, like the Americans, to build the ships on the lake itself, but even that task involved formidable transport challenges, with heavy materials such as guns and iron ballast having to be hauled overland to Kingston from the downriver ports of Quebec and Montreal. The completion of the two frigates and the ship-of-the-line launched at Kingston in 1814 was an astonishing achievement, but not one to provide a model for future emergencies.

A photograph of Lock 21 looking east, thought to have been taken about 1904. The buildings to the left are on the site of the present information pavilion, with the water level today being about a metre higher than the top of the embankment. Our dive in the video took us down the slope to the railing at the top of the weir, then over the railing to the bottom of the canal, through the sluice gates (underwater in this photo) and out the other side (photographer unknown).

A view of Lock 21 looking in the opposite direction to the photo above, with the US bank of the St Lawrence in the background. We're standing close to the site of the buildings about the embankment seen in the 1904 photo. The concrete block in the foreground marks the eastern end of the lock, with the block just visible about a hundred metres upstream marking the western end at the weir and the entry point for divers.

The first canal system in Canada, the Rideau Canal between Kingston and Ottawa, was itself a military conception, designed to provide a line of communication and transport in the event of war and planned by the Royal Engineers. By the time the Cornwall Canal was built, in 1834-42, the threat of war had receded, and the overwhelming need was to provide better transport and trade between the Atlantic and Upper Canada. The advent of steamships hugely increased the rate of traffic, and soon the original nine-foot depth of the canal proved inadequate. From 1876 to 1904 the entire eleven and a half mile length was deepened and widened, with Lock 21, the first lock at the upper end of the canal, being completed in 1886, allowing ships through with a draft of 14 feet and up to 245 feet in length, with cargoes of about 2,500 tons.

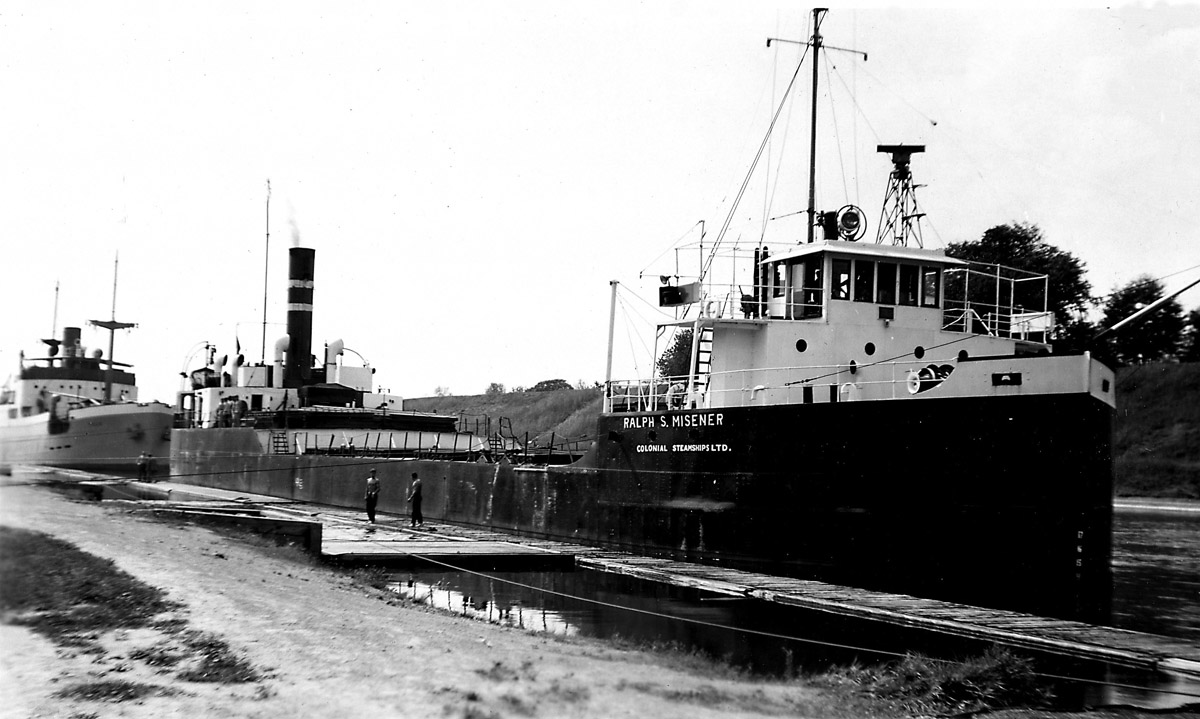

The vital importance of the the canal throughout this period and into the 20th century is shown by the attention paid to it in the Public Works proceedings of Parliament, and in many photographs showing ships passing through the locks in both directions. The following four photos of Lock 21, all thought to have been taken in the early 1950s, show 'lakers' and 'salties', the former the distinctive barge-like boats of the Great Lakes and the latter small ocean-going freighters (photographers, from left: Dan McCormick; Jim Kidd; Dan McCormick; unknown).

A plan of Lock 21 for divers on display in the information pavilion at the site. For our dive seen in the video we followed the rope down to the weir, went through the sluice gates and came up the other side.(plan: N. Baets).

The final transformation of Lock 21 took place over a few days in July 1958, when the canal and many surrounding villages were inundated to create the head pond for a hydroelectric dam near Cornwall as well as to raise the river level for the new St Lawrence Seaway. The river current, such an impediment to early shippers, was thus put to good effect as an electricity generator, and the construction of the wider channels of the St Lawrence Seaway allowed larger ocean-going vessels to get through. The Lost Villages have also become a dive attraction, and a number of the pioneer houses that were saved from the flooding can be seen today at Upper Canada Village.

We easily found the entry point to Lock 21 off the Long Sault Parkway, as the site marked by a plaque and an information pavilion set up for divers. After kitting up we waded out along the top of the former canal embankment and found the guide rope for divers that led down some twelve metres to the railing above the weir. The rope proved essential against the current, which was running at some three knots over the weir – impossible to swim against, and strong enough to pull my pony bottle regulator out of its retainer beneath my neck and leave it dangling behind, as you can see in the film. Once we had made our way over the lip of the weir and dropped to the floor of the canal, a little over 18 metres deep, we were out of the main force of the current and able to appreciate the massive structure in front of us. The most striking features were the sluice channels of the weir, and Alan filmed me while I rocketed through one of them with the current and then clawed my way back in order to allow him to film me doing it again from another angle. By then the exertion had depleted our air, and once he had followed me through we made our way back up the slope against the current towards the surface. You can see all of this in Alan’s excellent video.