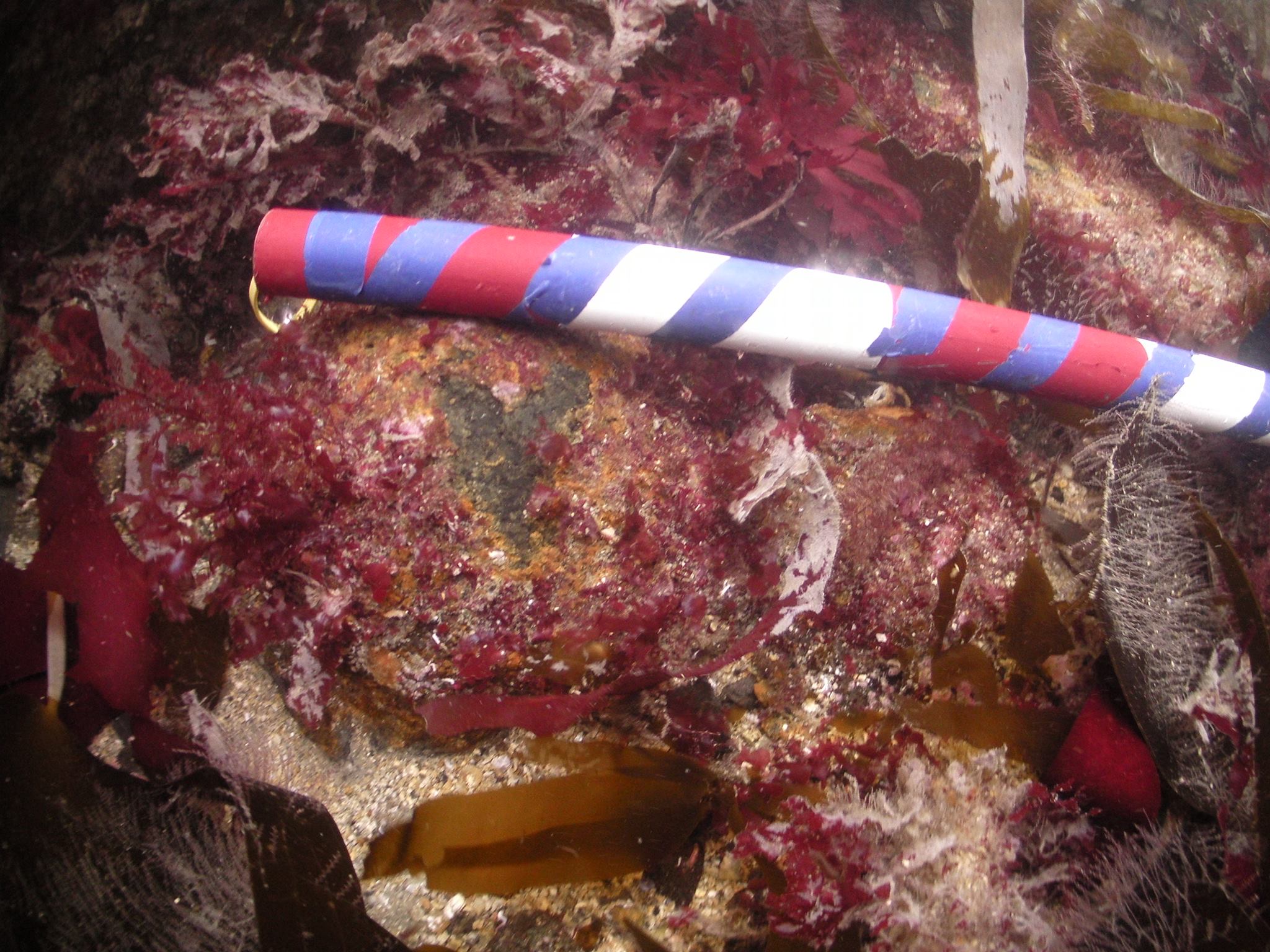

In July 2016 Mark Milburn and I dived with our team from Cornwall Maritime Archaeology on the wreck of HMS Primrose, a Royal Navy sloop that struck the Manacles south of Falmouth during a winter gale in 1809. Of some 126 crew and passengers aboard, only one person survived. The wreck was extensively salvaged by divers in the 1970s, and during our dives only a few artefacts were visible among rocky fissures and gullies at about 12 to 15 metres depth, under dense growths of kelp. Our dives were carried out in conjunction with an evaluation of the site for Historic England by Wessex Archaeology, and in this video by Jeff Goodman of Scubaverse you can see footage taken on that day. The photos by Mark below show cannonballs heavily accreted to the seabed, and illustrate the difficulty of identifying wreck material at this site (click to enlarge).

The Primrose is summarised on the Historic England site Pastscape, including lists of declared finds, but a detailed report on the wreck has never been published.

History

HMS Primrose was a Cruizer-class brig-sloop built at Fowey, Cornwall, by Robert Nicholls, and launched on 5 August 1807. She was 100 feet 6 inches in length, 30 feet 6 inches in beam and 384 tons burden, had a crew of 121 and was armed with sixteen 32-pounder carronades and two 6-pounder bow-guns. No depictions are known of Primrose herself, but the Admiralty Collection in the National Maritime Museum contains several plans of Cruizer-class vessels - including the one shown at the top of this blog - of Primrose’s batch, as ordered by Admiral Barham’s Board and launched in 1806-7.

The Cruizer-class were the most numerous Royal Navy vessel built during the Napoleonic Wars, with 110 vessels being built to the original 1797 design. At a time when the Royal Navy was suffering severe manpower shortages, the Cruizer-class was attractive because the brig-rig – with only two masts, the fore and the main, by contrast with the three masts of a ship-rig – required fewer men to manage, as did the carronades compared to long guns. These features, though, were also the ships’ main drawbacks; the carronades were devastating at close quarters, giving Cruizer-class vessels the firepower of a small frigate, but at longer ranges an opponent with a main armament of long guns would have the advantage. Moreover, whereas a ship-rigged vessel could survive the destruction of one mast and still manoeuvre, a brig-rigged ship without one of its masts would effectively be disabled.

This depiction of HMS Recruit, another one of the batch of 17 Cruizer-class brig-sloops built to the Barham's Board design in 1806-7, gives an excellent impression of the appearance of HMS Primrose. The two-mast brig-rig can clearly be seen, as well as the portholes for the carronades. The caption reads 'Intrepid behaviour of Captn Charles Napier, in HM 18 gun Brig Recruit for which he was appointed to the D'Haupoult. The 74 now pouring a broadside into her. April 15 1809.' Recruit survived this action, and was sold in 1822 (etching, George W. Terry and George Greatbach, National Maritime Museum PAD5779)

As with other wrecks of this period, the loss of HMS Primrose occasioned a literary epithet - in this case an ode on the unfortunate Colonel Tucker, who, as the anonymous author of this review in The British Critic opined, 'deserved a much better poet.'

Under Commander James Mein, Primrose sailed for Spain on 3 February 1807 and took part in an action on 14-18 May in the Tagus river in which she rescued the crew of another brig sunk by a shore battery. On her final voyage she sailed again for Spain as a convoy escort, leaving Portsmouth on 5 January but coming to grief in a snowstorm against Mistral Rock in the Manacles at about 5 am on 22 January: ‘She struck on the outer rock of the Manacles, drove in on the shallow ground and sank.’ Despite the efforts of the Manacles Signal Post officer and a boat manned by six local fishermen, there was only one survivor, a seventeen-year old boy named John Meaghan. The newspapers reported the following day that ‘His Majesty’s Brigs Swallow and Sparrowhawk sailed last night to endeavor to save what remained of the crew and stores of the unfortunate Primrose, and returned this evening, nothing remaining above water; the Primrose’s mast heads are just above the high water mark; the poor little boy, who is the only survivor, was taken off from the royal mast head.’

Among the six passengers were two brothers, Lieutenant Colonel George Tucker and Captain Nathaniel Tucker, two of five brothers serving in the army at that time and both returning to Spain for the Peninsular War. On the same night another ship was lost on the Manacles, the Dispatch, containing a contingent of the 7th Dragoons returning from Spain. Many bodies from both wrecks washed up on shore, and more than a hundred were buried in nearby St Keverne churchyard where the memorial stones can be seen today.

Artefacts from the wreck

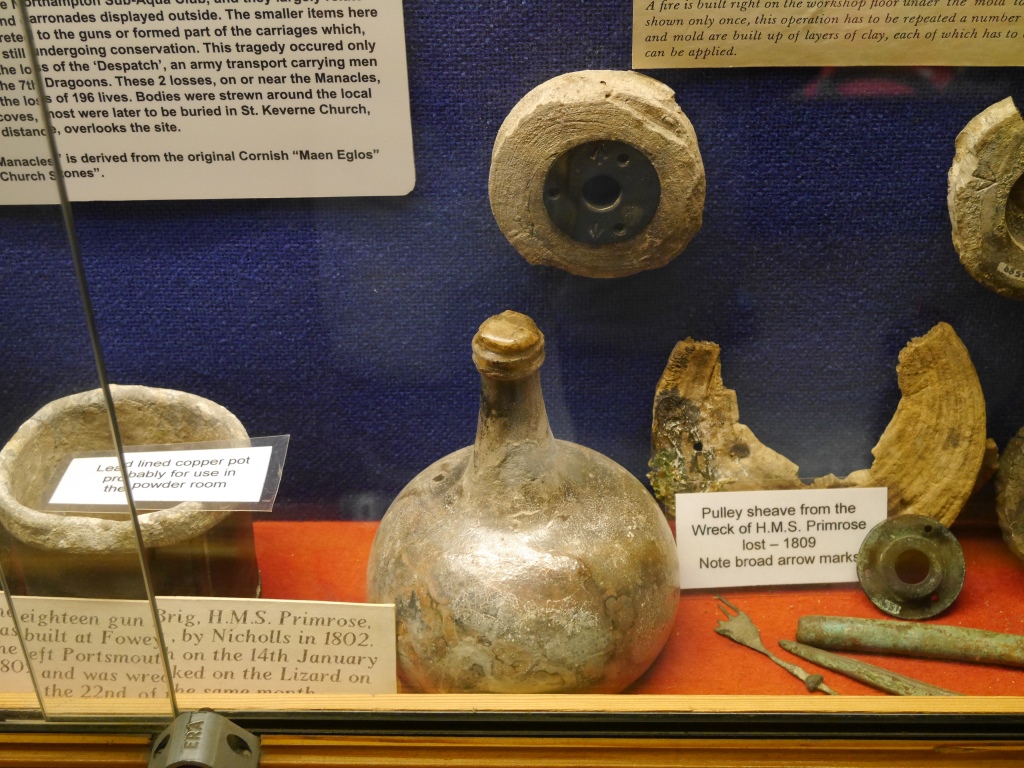

A collection of finds attributed to this wreck are on display in one cabinet in the Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre. The caption states that ‘The items in this case have been recovered from the wreck site in the last few years with the help of the Northampton Sub-Aqua Club, and they largely relate to the two 32 pound carronades displayed outside. The smaller items here were either concreted to the guns or formed part of the carriages, which, being wood, are still undergoing conservation.’ It seems likely that this display was created about 1980, as the main period of salvage by the Northampton club was in the late 1970s. At some point in recent years the two carronades were moved from outside the museum, and their whereabouts now are unknown.

The cabinet contains finds from other wrecks, in the vertical display above the caption and on the lower shelf. Among the unlabelled artefacts on the shelves with Primrose material are two intact onion bottles, a form that would normally be dated to the 17th or early 18th century. Of the other artefacts, a small copper-alloy gun found by diver Reg Dunton at or near the site in 1963 may well be from the wreck - it may be a boat gun - but more detailed study is needed to establish whether it can be independently dated and its place of manufacture established ( the caption identifies it as of Danish origin, but the basis for that identification is not stated).

Artefacts from Primrose are displayed in the lower part of the upper case and the top shelf of the lower cabinet (Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre). Click to enlarge; see below for close-up views.

The comment in the display cabinet caption about the gun carriages and artefacts being found in concretion provides evidence for site formation. During our dives we saw only a few places where extensive burial of artefacts in stable sediments might be expected; most of the site was a highly variegated seabed of exposed rock, with much accretion. The rapid formation of ferrous concretion from the iron carronades over the gun carriages, preserving both the wood of the carriages and other artefacts nearby, including organic materials, would explain the survival of these materials in such an exposed site. Taking into account contemporary news reports that the ship was resting upright on the seabed - the mast-tops exposed above the surface - this suggests that the wreck may not only have retained a wide range of artefacts preserved in concretion, but also a degree of distributional coherence reflecting the dimensions and layout of the ship.

The artefacts pictured below, from left to right in the upper part of the display cabinet, include a pewter plate, copper or copper-alloy pins, a name plate for a 32 pound carronade, two onion bottles (one still stoppered, and both of questionable association with this wreck), a lead-lined copper bowl (perhaps for lading gunpowder), wooden pulley and sheave blocks, an intact leather shoe and another bottle (click to enlarge).

The gallery below, left to right in the lower cabinet, shows lead shot for pistol and musket as well as grape-shot, weights, cast-iron slewing wheels for the carronades, metre-long copper hull-fastening pins, a small copper-alloy gun with a three-inch bore, a photo of Reg Dunton with the gun in 1963, pieces of breeching rope for the carronades and a wooden tompion with its spunyarn plug found in the muzzle of a loaded carronade (click to enlarge).

The photos below show a carronade being raised from the wreck of Primrose, perhaps by Northampton BSAC in 1978; a carronade and cannonballs after cleaning; two carronades said to have been from the wreck at the Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre (now missing); and a cannonball said to be from the wreck.

St Keverne church contains a copper gudgeon said to have been from the wreck, shown below, as well as a 32-pounder carronade at the front of the churchyard. The carronade is believed to have been raised in 1978 by Northampton BSAC - perhaps shown in the photos above - and to have been installed in the churchyard in 1980, where it has remained apart from its removal recently for refurbishment by local volunteers (it was reinstalled in 2017, when the pictures below were taken). The carronade is mounted on a facsimile of a slider carriage (missing the elevation thread, the hole for which can be seen in the pommel in the second photo); the date 1801 is said to have been visible on the gun when it was raised.