SS Gairsoppa (1941)

ss gairsoppa (1941)

This page contains additional material and images for Chapter 12 of my book A History of the World in Twelve Shipwrecks.

When I first moved to the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall to dive on shipwrecks, one story from the Second World War stood out among all the others told by locals. On 1 March 1941, three evacuee schoolgirls walking near the cliffs above Caerthillian Cove saw a ship’s boat being driven in by the swell. One girl ran down to the cove to shout encouragement to the men in the boat, and another to Lizard village to find the coastguard. By the time help arrived the boat had upturned and only one of the five men aboard was dragged alive from the sea. He was Richard Ayres, Second Officer of the SS Gairsoppa, sunk by a German U-boat two weeks earlier some 240 miles off the coast of Ireland – one of over 4,700 British-flagged merchant ships and fishing vessels to be sunk by enemy action during the war. The citation for the M.B.E. (Member of the Order of the British Empire) awarded to Ayres, who steering the boat west as more than 25 men died of cold and dehydration, described how ‘Undismayed by suffering and death, he had kept a stout heart and done all he could to comfort his shipmates and bring them to safety,’ in a feat of endurance that the Secretary of the Honours and Awards Committee called ‘one of the starker episodes of the war.’

The SS Gairsoppa once again came to widespread attention when the wreck was discovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration in 2011 more than 4,700 metres deep on the abyssal plain. Not only were they able to recover a large part of the ship’s cargo of silver bullion – one of the most valuable cargoes ever to be raised from the seabed – but the archaeologists also recorded many aspects of the ship and her equipment. The Gairsoppa is the first Allied merchantman of the Second World War to have been investigated in abyssal depth, and because of its state of preservation gives an unparalleled picture of a ship of this period. Among the outstanding finds were a cache of letters, laden at the ship’s port of origin in India and destined for Britain and the United States. Many of these letters have been published in a fascinating book edited by Dr Sean Kingsley, Voices from the Deep. The British Raj & Battle of the Atlantic in World War II (2018). You can listen to him talking about the letters on Wreckwatch TV and see much additional material on the webpage set up to accompany an exhibit of the letters at The Postal Museum, including photos of the work carried out by Odyssey Marine Exploration at the site.

A number of the document images below from my research in The National Archives on the Gairsoppa’s convoy and the ship’s crew have not previously been published. I am very grateful to Dr Sean Kingsley for much assistance in the research for this chapter, and to him and Greg Stemm for permission to publish three photos of the wreck in the book.

Click on the images to enlarge:

The only known photo of the Gairsoppa, taken between the wars in her peacetime paint scheme including the distinctive striped funnel of British India Co. She was built in 1919, had a gross tonnage of 5,257 and was driven by a single screw powered by a triple-expansion steam engine. For her final voyage, she had a crew of 84 - made up of British officers and Indian ‘Lascar’ ratings - and two D.E.M.S. (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship) gunners.

The ‘Master’s Ticket’ of Gerald Hyland, Captain of the Gairsoppa at the time of her sinking. He was aged 40 and is listed on panel 51 of the Merchant Navy Memorial to the missing at Tower Hill in London along with the other 10 British members of crew; the Indian men are commemorated in memorial books in Chittagong and Bombay, the one Chinese man on the Hong Kong Memorial to Chinese merchant seamen and the Royal Marines gunner on the Chatham Naval Memorial.

The Indian (Lascar) deck crew on the Gairsoppa’s final voyage, including the Serang and Tindal - equivalent to Bosun and Bosun’s Mate - and showing their origin, many from the island of Sandwip near Chittagong in present-day Bangladesh (BT 381/1361, The National Archives).

The convoy sailing order for SL 64 from Sierra Leone in February 1941, showing the Gairsoppa in second position in the second column from the left. Many of these ships did not survive the war (ADM 199/1943, The National Archives).

The last-ever reference to the Gairsoppa in the convoy commodore’s report, showing that she was not the only ship to detach from the convoy and disappear over those days (ADM 199/1943, The National Archives).

Chart from the war diary of U-101 showing the patrol in which it sank the Gairsoppa, with the position in in the centre (‘Dampfer’ means steamer). The line of 50 Degrees North closely represents the course of Ayres and the boat towards Cornwall (Bundesarchiv-Abt Militärarchiv, Freiburg).

Photo taken for the press at the time of two of the girls and Coastguard Brian Richards pointing towards the site at Caerthillian Cove where Richard Ayres was rescued.

Painting by Richard Eurich of the scene in Caerthillian Cove on 1 March 1941, entitled ‘Rescue of the Only Survivor of a Torpedoed Merchant Ship.’ Eurich was an official war artist, and showed the painting during a press event in London on 28 May 1942 when he wrote that it attracted ‘a good deal of attention’ (as I show in my chapter, the story of Richard Ayres’ survival was widely covered in the press both immediately after the event and when he was awarded the M.B.E.). Eurich had either been to the cove or was working from a photograph, as it is accurately shown though with the boat and men larger than they would be in real life (Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, Yorkshire).

Caerthillian Cove, where Ayres’ boat upturned and he was rescued. The photo with the girls shows them on the far headland looking in this direction, and the painting by Eurich also was a view from the opposite side of the cove. The view in this photo is almost due south, towards the end of Lizard Peninsula about half a mile away; the boat had come in off the Atlantic from the west (photo: David Gibbins).

Richard Hamilton Ayres, Second Officer of the Gairsoppa at the time that she was sunk. Born in 1910, the son of a merchant captain, he joined the school ship HMS Worcester aged 15 as a Royal Naval Reserve Cadet before going to sea as a deck officer with British India Co. Following his rescue, in his own words, ‘after 9 months on 100% disability pension I returned to sea with the B. I., and later R.N.R., and after the war was offered a job as a cargo superintendent in India and later Malaya.’ As well as the M.B.E. he was awarded the Lloyds War Medal for Bravery at Sea.

Approval of Ayres’ award (ADM 1/11456, The National Archives).

This and the following two headstones in Landewednack churchyard mark the burials of men who were in the boat with Ayres but did not survive after it capsized. This stone represents one or possibly two Indian sailors whose names were not known at the time of the burial. In a letter written in 1990, Ayres wrote "Whilst I was in Helston Cottage Hospital, I was interviewed by someone in authority to establish the identities of the bodies that were recovered, both Asian and European, but as I was incapable of walking this was not possible and they were buried after I had given my descriptions. The Asians, who were Mohammedans, were buried at my request in accordance with their religious rites, i.e. east-west facing Mecca.’ The record of these burials can be seen at the Commonwealth War Grave Commission website (photo: David Gibbins).

The grave of Norman Thomas, Seaman Gunner, whose parents decided to keep their stone rather than have it replaced by a Commonwealth War Graves one after the war (photo: David Gibbins).

Richard Hampshire’s grave at Landewednack. The dates given, from the date of the sinking of the Gairsoppa to the date of the recovery of his body, allow for uncertainty over the actual date of his death, but Ayres’ account makes it clear that Hampshire was still alive when the boat upturned in Caerthillian Cove on 1 March (photo: David Gibbins).

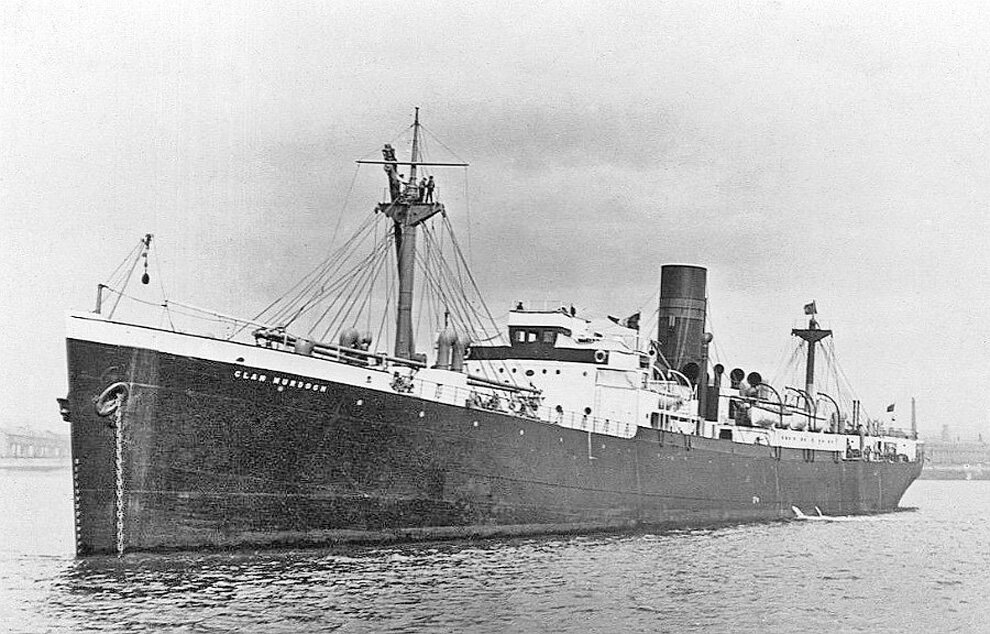

In the chapter I also mention the experience of my grandfather in a convoy from Sierra Leone only two ahead of SL 64, with his ship the Clan Murdoch being under German air attack on the day that the Gairsoppa was sunk. You can read more about that here: