The Boyne (1873)

A nautical chronometer with its wooden box discovered by Ben Dunstan on the Boyne during our first dive together on the site in 2020 - one of the most remarkable finds ever made from a shipwreck off Cornwall. Click to enlarge and see below for more images.

THE BOYNE (1873)

The Boyne is one of the most fascinating of the 19th century wrecks that we have investigated off the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall. Wrecked on Meres Ledges off Angrouse cliffs just north of Mullion at about 5 am on 1 March 1873, she was an iron-hulled barque of 617 tons measuring 150 feet in length. She was bound for Falmouth after a voyage of some four months from Samarang in Indonesia, where she had picked up a cargo of 900 tons of sugar on behalf of her owners, W.H. Tindall & Co of Scarborough.

After passing Wolf Rock Light off Land’s End and seeing the Lizard light, the ship’s master, Captain John Whelan, had been confident enough that they would clear Lizard Point that he had gone below to his cabin at 4.15 am, whereas in fact they were off course and heading into Mount’s Bay – something that had not been ascertained at night and in ‘thick weather’, with rain and fog and a half-gale blowing west-south-west. She had been travelling with a heavy following sea and struck the rocks head-on, thereafter quickly broaching to and parting midships; the tide had been high but with the ebb the stern slipped off the rocks into deeper water. The captain had ordered the boats lowered as soon as he was back on deck after impact but only the jolly boat put out, carrying four men who were to be the only survivors. By the time the coast guard arrived with a rocket apparatus for firing a line to the wreck and the Mullion lifeboat was on the scene it was too late to save the men still clinging to the wreckage, and all fifteen of the remaining crew including Captain Whelan perished in the sea and against the rocks.

The violence and horror of the wrecking was remarked on at the time: ‘Five of the drowned sailors … have been washed ashore more or less mutilated. A thigh and a hand have also been picked up. A sailor who survived stated that as the ship broke up he noticed one of his shipmates nearly cut in two’ (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 15 March 1873). The full text of the Board of Inquiry into the wreck is reproduced at the bottom of this page.

Heavy seas over Meres Ledges, site of the wreck of the Boyne. This was the place on Angrouse Cliffs where the coast guard would have attempted to use the rocket-fired line to rescue men clinging to the forward part of the ship on the rocks some 20 metres below. There is no way of climbing the cliffs at this point and the great difficulty for the Mullion lifeboatmen in laying their boat alongside the wreck can be imagined. The four survivors were not rescued from the wreckage but had set out in the ship’s jolly boat after the captain had ordered the boats lowered immediately after she had struck..

The ship’s bell, with the words Boyne and Scarborough clearly visible. This was recovered by a local man from the rocks of Meres Ledges on a spring low a number of years ago. We are very grateful to him for bringing this find to our attention and allowing us to photograph it.

A brass nameplate from the Boyne recovered in 1969, naming her port of registry as Scarborough. Maximum width 45 cm (photo courtesy Dave McBride).

The first page of a letter from Harland & Wolff of Belfast to W.H. Tindall on 17 January 1866, noting the ‘long list of Extras’ requested by Tindall, the bill of £28 14s and the fact that they were unable to acquire ‘the 4 square water tanks, and the two Carronades.’

The ship was built in 1865 by Harland & Wolff in Belfast, the second of two barques ordered by Tindall for their Far Eastern trade. The Lloyd’s Register Foundation has the 1871 Annual Survey Report for the ship. Several years ago a collection of documents was sold at auction related to the ship, including a plan, three letters from Harland & Wolff to Tindall in 1865-6 and contemporary documents related to the wreck. The whereabouts of most of this material is unknown, but fortunately a record was made of the summary of the letters in the auction catalogue. They show that Tindall had ordered a large number of ‘extras’ for the ship, including ‘a barometer, night telescope, muskets, pistols, cutlasses etc.’ This has proved particularly interesting in light of the finds that we have made at the site. The third of the letters is in a private collection and has been seen in its entirety. It contains the bill for the extras, £28 14s (about £4,176 in present value), with the exception of items that Harland & Wolff could not procure, ‘4 square water tanks and two carronnades.’

Peter McBride discovered the wreck in 1969 when he found a brass nameplate that identified the ship. I first dived there in June 2018 and explored it over several dives that year with Mark Milburn, and later with my daughter Molly. At that time the main concentration of artefacts seen was in a cleft only a few metres from the cliff face, in less than 5 metres depth. Our current investigations began in June 2020 when Ben Dunstan and I were swimming back from a dive on the nearby wreck of the Santo Cristo di Castello (1667) and saw brass artefacts protruding from previously unexplored gully. Over many dives since then from boats or from the nearby beach at Polurrian we have partly excavated that gully as well as another one closer inshore. These gullies would appear to represent respectively the stern and the forward part of the ship, with the artefacts in the seaward gully consistent with the captain’s cabin and stern quarters. These finds make up one of the richest assemblages of nautical equipment to be discovered from a shipwreck of this type and period, including a chronometer, nautical dividers, a telescope, muskets and medical equipment.

All of the artefacts shown on this page have been declared to the UK Receiver of Wreck in accordance with the requirements of the 1894 Merchant Shipping Act. Click on the images to enlarge.

This image of the iron barque the Palestine is in the National Maritime Museum (G2307) and the A.D. Edwardes Collection of ship photos held in the State Library of South Australia. It shows the ship moored probably off Gravesend in about 1875. She can be regarded as a sister-ship of the Boyne - they were both built at Harland & Wolff in Belfast for W.H. Tindall of Scarborough, the Palestine being launched in 1863 and the Boyne in 1865. One of the letters noted above from Harland & Wolff to Tindall in 1865 outlined the differences between the two ships. They were slight - the survey reports held in the National Maritime Museum show that the Palestine was 607.81 gross tons with a length aloft of 184 feet 3 inches and an extreme breadth of 27 feet six inches, while the Boyne was 617.48 tons, 185 feet 8 inches length aloft and 28 feet one inch extreme breadth. With the surveys showing that the rigging and hull construction were virtually identical, this photo therefore gives an excellent idea of the appearance of the Boyne as well.

This plan of the Boyne is only available as a very low-resolution copy made several years ago from an auction catalogue, and sent to us. It is on waxed paper stamped by Harland & Wolff and was auctioned along with contemporary letters and other documents related to the Boyne, as described above. If anyone seeing this knows the whereabouts of the original, we would love to hear from you! Even from this image it is possible to see the very close similarity with the photo of the Palestine in the image above.

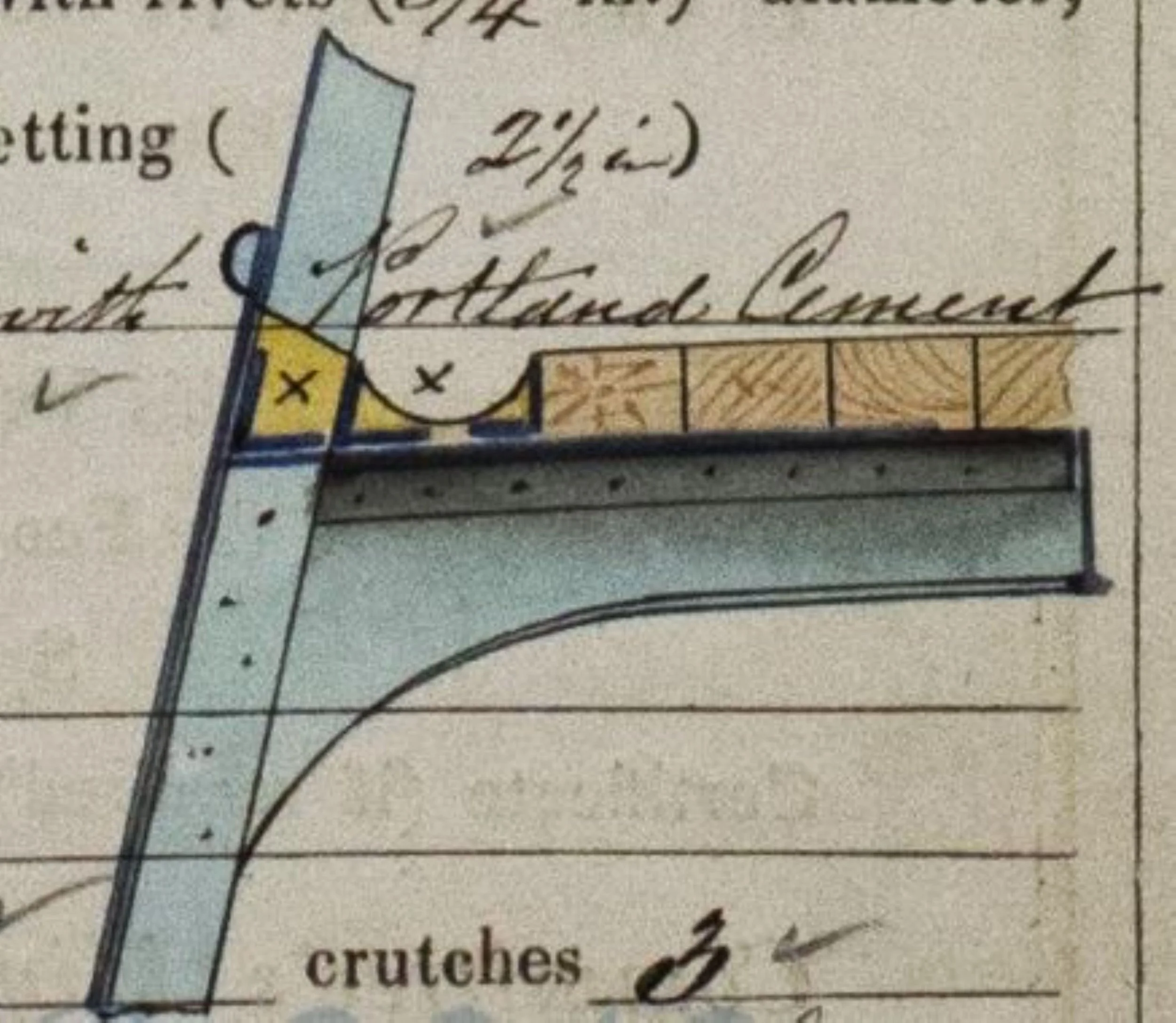

This watercolour of an iron knee with deck planking is a detail from the 1871 survey report on the Boyne, held by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

An advertisement for the maiden voyage of the Bone in early 1866 from London to Ceylon, where Tindall owned tea plantations. The description of this ‘splendid vessel’ with ‘full poop and accommodation of the first order’ is consistent with the quality of the fittings and artefacts found in the wreck (London and China Telegraph, 7 December 1865).

The Site

The wreck is spread over an area of approximately 20 by 50 metres, roughly consistent with the size of the ship, in less than 8 metres depth at low water. The seabed at this point is a continuation of the rocky shelf of Meres Ledges visible in the photo above, with gullies and deep fissures filled with boulders and shingle. The main area of the site comprises one central gully about 25 metres long with a number of side gullies, labelled A, B and C, and a further, separate gully, labelled D - a large pothole in the reef about three to four metres deeper than than the upper surface of the reef, and big enough to fit a small car inside. The nearest sandy seabed is some thirty metres distant in the direction of Polurrian, too far for storms to lift significant amounts of sand and deposit them on the site - one reason for the poor preservation of the wreck in general other than in the side gullies.

Other than certainty that the outermost gully, B, contains artefacts from the stern of the ship, consistent with the account of its breakup after the wrecking, there is little distributional coherence in the wreck. Segments of iron plating and ironwork are wedged under overhangs and concreted into the seabed, as visible. In general, it is remarkable how little of the ship survives, compared to other iron ships that we have dived on off the west coast of the Lizard - testament to the extreme exposure of Meres Ledges and the likelihood that much of the ironwork was never buried and therefore quickly corroded away. On the other hand, the preservation of artefacts in Gully B was remarkable. As can be seen in the images below, the gully is deep and protected on the seaward side by a rocky outcrop that almost forms a small cavern in which much of the material has been found, including extensive remains of wooden items preserved through being buried deeply in sand or in the ferrous concretion that sealed in much of the deposit in the gully.

A view of the southern, outer part of the site in conditions of excellent visibility, showing the entrance to Gully B in the right foreground and Ben examining Gully C beyond that. There are no large structural remains visible from the surface or areas of flattened plating as are often seen on iron wrecks in high energy environments, with most of the ship structure at this site evidently having been dispersed, corroded away or salvaged at the time.

Iron girders and other elements wedged beneath a rocky overhand, along with a resident lobster.

An iron bar, perhaps ballast, adhering to a rock in Gully C, a deep pit in the reef filled with rock and shingle with other artefacts beneath.

Gully D, the most southerly on the site, showing the appearance of ironwork on the site with little recognisable form remaining and the iron embedded in concretion caused by its decay. The gully is approximately three metres long.

Concreted iron and a copper pipe in Gully A.

Gully A

The most obvious wreck material, first seen by us in 2018, lies in a cleft going in to shore from the outer edge of Meres Ledges, which is awash or exposed at low water. When there is no surge it is possible to swim up this cleft to within a few metres of the base of Angrouse Cliffs. With the ship having struck the rocks at high water, when the top of the Ledges can be five to six metres deep, it is easy to see how the entire forward part of the ship could have ridden a storm swell over the rock until the bowsprit struck the cliff face, and for it then to fall back and swing broadside-on against the outer edge of the Ledges before splitting in two. The material in Gully A would therefore represent structure and artefacts from the forward half of the ship. We have not attempted to excavate this gully because the ferrous concretion is rock-hard and there are no artefacts protruding from it that merit the time and effort involved, with two of the other gullies being our main focus.

Molly Gibbins in Gully A facing towards shore, showing the mass of rock-hard ferrous concretion that fills the floor of the gully.

Concreted iron in Gully A.

Gully B

The gully that Ben Dunstan and I first spotted in 2020 lies on the seaward, south-west side of the site, about 30 metres from Gully A and almost certainly where the stern of the ship ended up. In these photos you can see images of the gully as we first saw it with protruding brass artefacts and then over subsequent dives as it was excavated, up to the summer of 2024. In an area less than two metres square, this gully has proved the most productive in high quality artefacts of any wreck that we have investigated off the Lizard Peninsula. Many of the artefacts were preserved as a result of being embedded in ferrous concretion that had formed around them, and others were in a sandy layer between the concretion and the bedrock.

Gully B as seen for the first time by us in June 2020, with brass artefacts protruding from the sand. These proved to be parts of light fittings, as described among the ‘extras’ provided by Harland & Wolff for the ship in 1865 (David Gibbins).

Gully B on the first day of excavation after sand had been wafted away from the concretion, revealing a telescope and other artefacts (Ben Dunstan).

A musket emerging from concretion during excavation of Gully B (Ben Dunstan).

A view of Gully B from the surface in exceptional visibility, showing the protected overhand at the western end that helps to account for the preservation of artefacts protected from the surge and wave oscillations. The gully is approximately 4 metres long (David Gibbins).

Ben Dunstan excavating at the western end of Gully B, with the impressions visible in the concretion to his left where artefacts have been removed (David Gibbins).

A close-up of Gully B during excavation showing the outline of an iron box embedded in concretion, and above it a fragment of wood (David Gibbins).

A close-up of Gully B during excavation showing a brass object protruding from concretion (David Gibbins).

Artefacts from Gully C

As well as the Hong Kong coin above, excavation of Gully C in 2020-1 produced a large number of brass objects including ship’s fittings and furniture fittings. This gully was located some 30 metres from Gully B at the northern end of the site, and may represent part of the bow assemblage - perhaps artefacts from the crew quarters - after she had broached to against Meres Ledges with the bow facing north.

The full report of the Board of Inquiry held at Greenwich on the loss of the Boyne, ‘Stranded about one and a half miles N & W of Mullion Cove, near the Lizard, on the 1st of March 1873 (Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Vol. 61, 1874, p. 96).