Archaeology

Archaeology

Click on images to enlarge

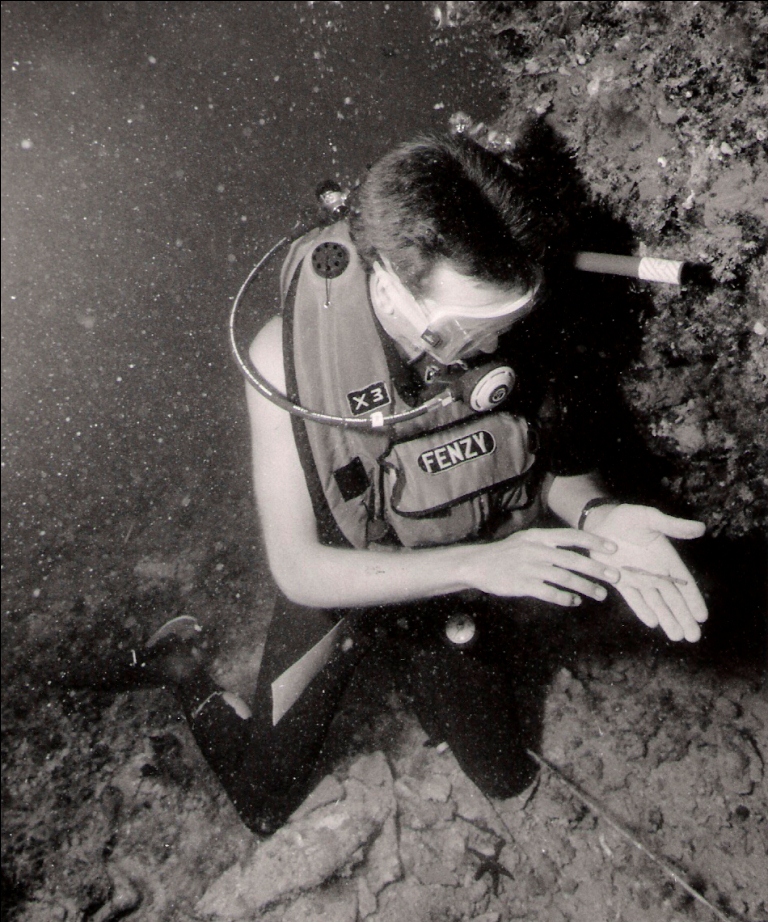

Photo of me at 30 metres depth off Sicily holding an ancient Roman bronze scalpel, uncovered from the gully at my knees (photo: Dr Chris Edge).

My passion for archaeology goes back at least as far as my fascination with diving; I’d begun collecting artefacts and searching for ancient sites long before I received any formal training in field techniques. My first discovery was as a small child in New Zealand, when my parents took me to a prehistoric site near our home in Nelson on the South Island and I found stone tools and flakes. As I write this one of my most recent discoveries has been a stone tool from a prehistoric site in Canada, so I remain true to my roots! Another formative experience as a child was in England at the Roman site of Wroxeter, where an enlightened museum curator allowed me to choose a piece of Samian ware to take away – something unimaginable today, but which had a profound effect on me. After that I began exploring the countryside around our home in rural Herefordshire, finding Neolithic flints and Roman coins, and back in Canada as a teenager I spent much of my time outside school searching derelict farms in southern Ontario for flint tools, Victorian bottles and other artefacts, as well as collecting coins, medals, fossils, antiquarian books, powder and shot flasks and virtually anything else old I could lay my hands on.

That early passion for artefacts was as important for my development as an archaeologist as the formal training I received, and remains as strong as ever. As I research and write my novels I always have artefacts with me from the period of my fiction – a blackened prehistoric sherd from Troy for The Mask of Troy, a Victorian medal given to a British soldier in Egypt in 1885 for Pharaoh, a coin minted in the year of the destruction of Carthage for Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage. Touching and contemplating artefacts has always been my portal to the past; I can still smell that sherd from Troy, an acrid odour that drew me into those final apocalyptic hours in the Homeric story as the citadel burned and Bronze Age civilisation in Aegean began to collapse.

The Roman scalpel shown in the image above. The blade on the left is a 'blunt dissector', and on the right there would have been an iron knife. This is one of the finest Roman surgical instruments ever found, and the only one of this type to have been discovered on a wreck - probably the belongings of a travelling doctor, perhaps a specialist eye-surgeon. Length: 8.5 cm.

My first formal training in field techniques took place on a summer course when I was fourteen, excavating a lakeside pioneer settlement in Ontario where I also had my first experience of archaeology underwater, free-diving for Victorian bottles and other artefacts on the lakebed. When I was eighteen I went to the University of Bristol in England to study archaeology and ancient history, graduating in 1983 with a first-class honours degree in Ancient Mediterranean Studies, and I then completed a PhD in Archaeology at Cambridge University as a Research Scholar of Corpus Christi College. After holding a Research Fellowship in the Faculty of Classics at Cambridge I worked as a university lecturer in England, including six years at the University of Liverpool teaching archaeology, ancient history and art history, until I left academia to write novels.

Stone tools at least 5,000 years old from a site in Ontario, Canada, investigated under my direction since the mid 1990s.

I was fortunate that my university education was wide in geographical and temporal scope, and exposed me to diverse approaches to the past. At Bristol my personal tutor, Dr Toby Parker, author of Ancient Shipwrecks of the Mediterranean, was the only academic in Britain at the time specialising in the maritime archaeology of the Mediterranean; I was also taught by Professor Peter Warren, director of excavations at Knossos in Crete, by James MacQueen, author of The Hittites and Babylon, and by Brian Warmington, whose book on Carthage touched off my fascination with the archaeology of Roman North Africa. During my time at Cambridge the Department of Archaeology included Colin Renfrew and Ian Hodder, while archaeologists in the Classics Faculty included Professor Anthony Snodgrass and my supervisor, Henry Hurst, Director of the British Mission in the UNESCO ‘Save Carthage’ project. The synergy then developing at Cambridge between prehistoric and classical archaeology resulted in many new ways of looking at the past, ranging from economic models and landscape archaeology to symbolism and art; in the study of ancient Greece and Rome, archaeology was no longer the ‘handmaiden’ of history. At Cambridge my office in the Classics Faculty also housed the library of Professor Sir Moses Finley, and I was strongly influenced by the school of ancient economic research that he had inspired as well as by the work of Fernand Braudel and his followers. The collegiate system at Cambridge which brings together diverse disciplines also meant that some of my closest friendships were with students of other subjects, included philosophy and the biological sciences. All of this suited the wide range of my interests and continues to influence my archaeological thinking, as well as the scope of my fiction.

Excavations at Poulton, Cheshire, 1995. For several seasons I was responsible for more than 100 students at this site, part of my job as a Lecturer at the University of Liverpool. The site was a medieval chapel and burial ground associated with a Cistercian monastery, and also contained evidence of Roman and prehistoric occupation. To see the cover of our monograph report click here.

I considered myself a specialist maritime archaeologist from the time of my first expedition to the Mediterranean to excavate a Roman shipwreck in 1981, and after taking maritime archaeology as one of my undergraduate special subjects. Nevertheless, I've also carried out fieldwork on land, including the excavation of Roman-British and prehistoric sites, the management of a training project for students at a Cistercian monastery site in Cheshire, and excavations at the ancient harbours of Carthage. In 1994 I discovered a prehistoric site that has produced some of the earliest stone tools found in Canada - dating from soon after the end of the last glaciation some 11,000 years ago - and my annual investigations at that site since then have produced over 3,000 artefacts. Contemplating a site of that nature, far removed from my main focus on shipwrecks, has helped to keep my archaeological horizons broad, and in particular to explore ‘cognitive’ archaeology, trying to get into the minds of people in the distant past – something that has helped me to envisage the mental maps of hunter-gatherers as they ventured out on the sea in my novel The Gods of Atlantis. Another aspect of my archaeological experience has been extensive travel to study sites in the Mediterranean region and elsewhere, from the Arctic to South America, as important for my ideas as actual excavation work. You can read about some of that travel here.

From 1999-2000 I was an Adjunct Professor of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) and worked for two seasons on a 5th century BC wreck at Tektas off Turkey. This article I wrote for the journal Antiquity shows some of the spectacular finds we made at the site, including many intact items of pottery. Click to enlarge.

I’ve outlined my diving career on a separate page. In the Mediterranean I’ve worked on wreck sites of Bronze Age, Etruscan, ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine date, in UK waters on wrecks of Roman and early historic date, and elsewhere in the world on sites ranging up to the 20th century. I’ve also directed the investigation of submerged land structures, notably the ruins of ancient Carthage. One of my most extensive projects was the investigation of a Roman wreck with olive oil and fishsauce amphoras of about AD 200 at Plemmirio off south-east Sicily, surveyed and excavated by teams under my direction over several seasons. The wreck produced unique finds – including a Roman surgeon’s instrument kit, the first one found in a wreck - and was the first cargo assemblage of that period to be characterized in detail. It formed part of my doctoral dissertation on Roman seaborne trade and resulted in many publications, including articles in the journals Antiquity, The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Archaeometry, World Archaeology and New Scientist. It was also the basis for the wreck of St Paul in my novel The Last Gospel. The inspiration that I continue to draw from that project reinforces my view that fieldwork is as much about the stimulus to broader thinking as it is about the specific data of discoveries, with the artefacts taking on new meanings as my own perspectives develop and change - something that goes back to my childhood fascination with artefacts as 'portals to the past', and fuels my imagination as a writer of archaeological fiction.

The gallery below (click to enlarge) shows images from the Plemmirio wreck. Clockwise from upper left: me with an amphora at 50 metres depth; my drawings of two oil lamps, one stamped with the maker's name IVNDRA; African olive oil and fishsauce amphoras; Jenny Lobell with a nearly intact amphora; a sherd with the painted graffito EGTTERE, probably meaning 'for export'; a selection of finds from the wreck; an amphora stamped PP, probably the Praetorian Prefect of the region in modern Tunisia where it was produced; and a view of our boats over the site, just south of Siracusa in Sicily.

As well as reports arising from fieldwork, my academic publications reflect a broader interest in the nature of maritime archaeology as a discipline, and in the different ways of investigating the past that have influenced my perspectives as an archaeologist. Some of these ideas were brought together in a paper I co-write with Jon Adams in a volume of World Archaeology that we edited in 2001, my last publication as an academic before I became a novelist. Writing archaeological fiction has deepened my interest in how we reconstruct the thinking behind past behaviour, and also my own self-awareness as an archaeologist – one of the reasons why I think the biographies of individual archaeologists are so important, as they help us to understand not only the intellectual but also the emotional backdrop to their careers and the basis for their passion for the subject. As with so many other walks of life, it’s the insights, energy and charisma of a few outstanding individuals that have led to the greatest discoveries and pushed archaeology forward as a discipline, something I've tried to bring across in my novels.

An overgrown cannon from a wreck of likely 17th century date that I discovered in 2013. For more on this exciting find, click here.

I'm currently involved in two maritime projects, one to produce high-quality video of historic wrecks in the Great Lakes of Canada and the other to discover and investigate historic wrecks off south-west Cornwall in England, with a particular focus on the western Lizard Peninsula. In both places I'm interested in the impact of wreckings on the cultural interface between land and sea, something that can be explored within living memory. Several of the sites are in high-energy, inshore environments, where I’m also able to pursue an interest in shallow-water wreck formation that goes back to my earliest projects in the Mediterranean. Several are of 17th-18th century date, reflecting a fascination with the maritime world of that time that I’ve developed in recent years – including the East Indies trade, and Spanish export from the Americas - and the ways in which wreck evidence complements the historical record; it also feeds off my current interest in the literature and intellectual milieu of that period. Another objective is the discovery of wrecks in UK waters of ancient date, including Phoenician and Roman sites. Look to my blog for reports on these and other projects as they progress!

Over the years my field projects have been funded and supported by many bodies, including the British Academy, The British Schools of Archaeology at Rome and Jerusalem, the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, The Palestine Exploration Fund, The Society of Antiquaries of London, Cambridge University Classics Faculty, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, to all of whom - as well as to the many members of my expeditions - I'm extremely grateful.

For a list of my academic publications, click here.

Banner photo by Molly Gibbins of Italian wine amphoras at Pompeii, AD 79.