Burma Star, awarded to Captain L.W. Gibbins for operations in the Bay of Bengal, 1944

This is my fourth blog on the British assault ship Empire Elaine and my grandfather’s experience as her Second Officer under Combined Operations, the British naval command responsible for seaborne landings during the Second World War. Empire Elaine had been designed for the Ministry of War Transport (M/T) as an L.S.C. (Landing Ship Carrier), one of few heavy-lift ships purpose-built to carry L.C.M.s (Landing Craft Mechanised). Despite her military role, the crew of Empire Elaine - in common with other M/T ships - were drawn from the Merchant Navy and managed by a shipping company, in this case the Clan Line. In my previous blogs I’ve written about Empire Elaine’s role in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, and Operation Dragoon, the invasion of the South of France in August 1944; here I’m looking at the period between those operations when she was in the Indian Ocean, another case where the primary documentation for her activities is elusive because of the top-secret nature of all actions planned by Combined Operations during the war.

Before his death in 1986 my grandfather spoke to me about some of his experiences in the eastern war zone, in particular the severe monsoon conditions that forced Empire Elaine back to Bombay during her first attempt to sail west to Suez and back to the Mediterranean in July 1944, in preparation for Operation Dragoon the following month. As a peacetime officer with the Clan Line – arguably the last of the great East Indies shipping companies – my grandfather had an intimate knowledge of the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal, and Clan Line men knew as well as any others the dangers of these waters during the war, with three ships managed by the company being lost to U-boats in the Indian Ocean in 1943-4 - Clan Macarthur, Banffshire and Berwickshire – and with Japanese air, mine and submarine attack also taking a toll of Allied shipping there and in the Bay of Bengal.

Years after my grandfather’s death I found a copy of the official history of the Clan Line during the Second World War, Gordon Holman’s In Danger’s Hour (Hodder and Stoughton, 1948), with a report from Empire Elaine’s master, Captain Ernest Coultas, showing that after Sicily she had ‘… been on special service in the Indian Ocean, had carried an 85-ton tug and many landing craft to ports in the Eastern war zone,’ and had ‘run through the monsoon’ before returning to the Mediterranean for the South of France landings (p. 194). As with the Mediterranean operations, my first point of reference when I came to revisit my grandfather’s experiences was his personal distance log showing ports-of-call and mileages during that voyage. The excerpt below shows Empire Elaine’s entire voyage from Sicily through various ports in the east Mediterranean to Suez and then to Bombay, and after that a complex itinerary of short- to medium-haul voyages from Bombay to Ceylon and back, and north to Iraq and Persia, with his telling note after the first arrival in Bombay ‘on exercises and returning to Bombay (twice)’:

The Ship Movement Card, the official summary of a ship’s movements now kept in the UK National Archives, gives little away, apart from confirming a number of the port visits and their dates, and showing that – as with the Sicily operation – Empire Elaine continued to be ‘Allocated to S.T.A.6A, for the carriage of special military cargo.’ More clarification is given by Arnold Hague’s convoyweb, which allows Empire Elaine’s convoys and port arrivals and departures to be traced through the war. Although a secondary source, these convoy records are corroborated by everything I have seen among the primary documentation, including my grandfather’s log. They show that after having sailed independently from Aden on 9 September and arriving at Bombay on 16 September 1943, there is a two month gap before the convoy records show her departure from Bombay again, on a voyage to Colombo in Ceylon in 19 November. Another gap of a month occurs between the date of her return to Bombay on 21 December and her departure again for Colombo on 14 January 1944. The first of these gaps coincides with my grandfather’s note in his log, about being on exercises. The second is explained by the following entry in the Admiralty War Diary in the UK National Archives, noting Empire Elaine:

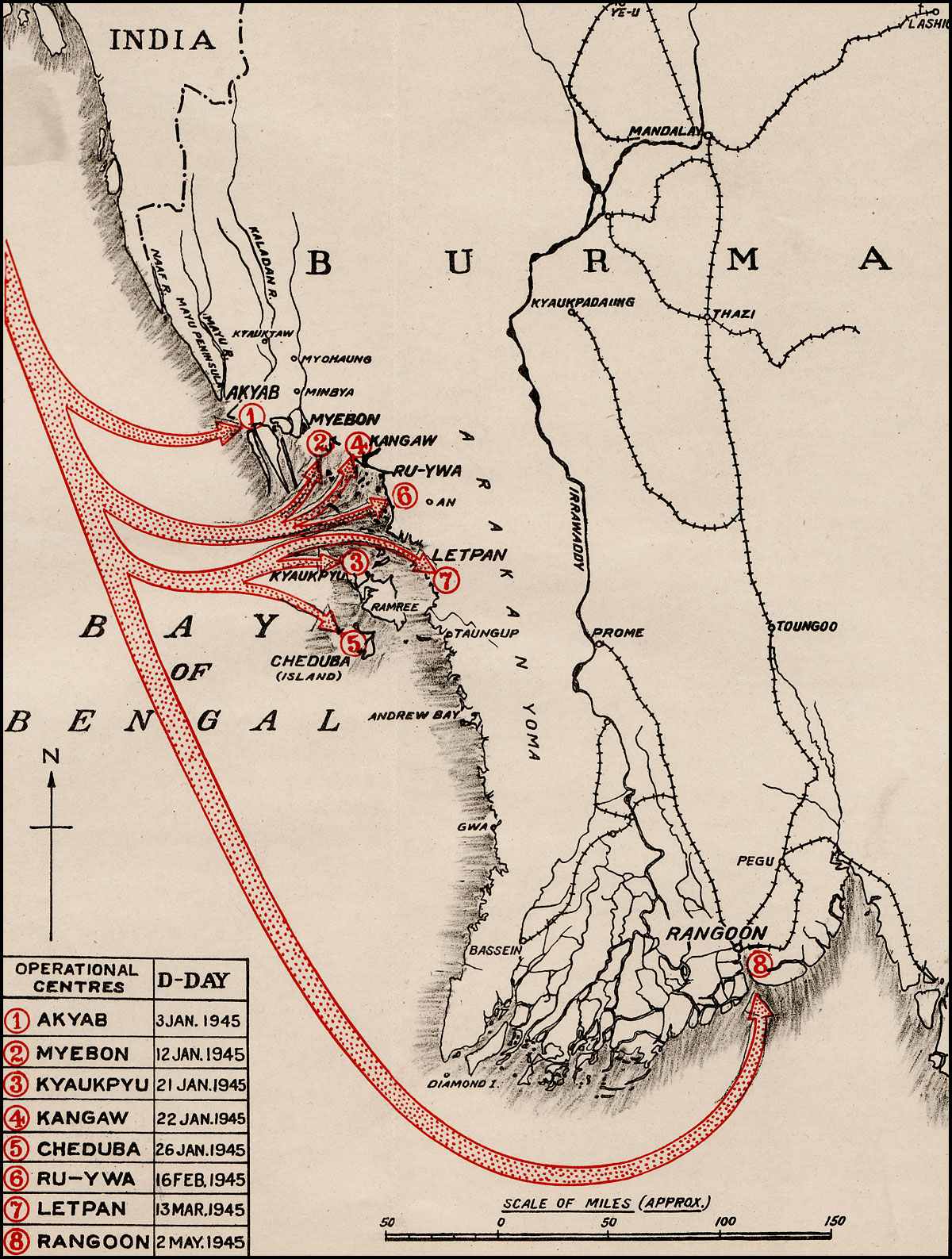

This entry explains the ‘exercises’ and proves that Empire Elaine was one of many vessels being assembled in the Indian Ocean in preparation for Operation Bullfrog, the codename for a planned assault on the Arakan coast of Burma in early 1944. The primary source material for the operation can be found in the UK National Archives by searching Operation Bullfrog, including ADM files on the naval planning. The objective, seen in the map below, was to land a division at Akyab Island (now Sittwe) at the base of the Mayu Peninsula, with the aim of cutting off the Japanese 55th Division as they advanced towards 15th Indian Corps to the north-west. Of the vessels listed with Empire Elaine in Force F, HMS Keren, HMS Denera and HMS Dilwara were troopships converted to L.S.I.s (Landing Ships Infantry), and HMS Boxer, HMS Bruiser and HMS Thruster were L.S.T.s Landing Ships Tank). Many of these ships had participated in the Sicily landings in July 1943 and the Salerno landings two months later (among her other achievements, HMS Boxer transported the comedian Spike Milligan from Africa to Italy with his artillery battery, as recounted in his 1978 autobiography Mussolini: His Part in My Downfall). Operation Bullfrog would therefore have been their third and possibly their most hazardous assault landing in only six months, had it not been cancelled in January 1944.

The circumstances of the cancellation are recounted in his book on the Burma campaign by General Bill Slim, the commander of 14th Army in Burma and one of the best generals of the war. My daughter’s maternal grandfather, a wartime officer in 4/15 Punjab Regiment, served under him as an intelligence officer during the retreat from Rangoon in 1942, and I have his well-thumbed copy of Slim’s Defeat into Victory with me now. In it Slim bluntly described a seaborne landing in Burma in early 1944 as ‘the correct strategy’, the linchpin of a seven-pronged offensive operation approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff at their Cairo conference in late November 1943. Unfortunately for Slim’s plans, only days later at the Tehran Conference Stalin insisted that he would only commit Soviet forces to the war against Japan if all efforts were directed first at defeating Germany. Churchill and Roosevelt accepted the condition, and ‘more than half the amphibious resources of South-East Asia were directed back to Europe’ (Slim, ibid., 213).

The consequence for Empire Elaine is recorded in the Admiralty War Diary of 26 February 1944: ‘S.A.C.S.E.A. (South East Asia Command) reports that the broad pendant of Commodore Douglas-Pennant as S.O. Force F was struck at sunset on 9th February and the Force disbanded.’ Tellingly, the very next entry reports news from the Arakan, revealing just the outcome that Slim had feared: ‘Heavy fighting is going on in the Arakan where the Japanese troops are attacking with the object of taking Chittagong.’ It was to Chittagong – the Allied supply port close to the Burma border - that Empire Elaine next went, carrying landing craft. Chittagong was under constant threat of air attack, and by the date of Empire Elaine’s arrival, 5 April 1944, the Japanese offensive into India was in full swing and the desperate battles of Imphal and Kohima were being fought to the north-east beyond the border in Assam. For the crew of Empire Elaine, sailing the last leg of the journey as a single-ship convoy from Calcutta to Chittagong, the perils of submarine attack would probably have been uppermost in their minds, even in a place so far from the main German U-boat threat. On the same Calcutta-Chittagong route less than two weeks earlier the Japanese submarine RO-111 had sunk the troopship El Madina, with 380 killed - an event horribly reminiscent of the torpedoing only a month before that off the Maldives by another Japanese submarine of another troopship, the Khedive Ismael, with the loss of almost 1300 soldiers and crew, one of the worst British maritime disasters of the war.

Map showing ambhibious operations undertaken by the Royal Indian Navy in 1945, including the landings at Akyab on 3 January - site of the cancelled Operation Bullfrog landings of a year earlier. Chittagong lies on the Indian coast at the top left corner. (From The Royal Indian Navy, 1939-45, part of The Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War).

Only days after the disbanding of ‘Force F’, one of the M/T ships, Fort Buckingham, also came to grief, torpedoed on 20 January 1944 by U-188 off the Maldives on her way back to the Atlantic, with the loss of her Master, Captain Murdo Macleod, D.S.C., thirty crew and seven gunners. Most of the other ships returned to the Mediterranean, some speedily enough to take part in the Anzio landings in Italy that month, and many to take part – along with Empire Elaine – in Operation Dragoon in August. At the time, the frustration shown in General Slim’s account must have clouded feelings about the time and effort spent preparing for Operation Bullfrog, but the additional experience and training it provided undoubtedly paid rewards. Commodore (later Admiral Sir Cyril) Douglas-Pennant was next to ‘hoist his broad pennant’ in HMS Bulolo – a ship well-known to my grandfather from a convoy earlier in the war, one that narrowly avoided an encounter with the German battleship Bismarck – when Douglas-Pennant commanded the assault force at Gold Beach in Normandy, on D-Day, 6 June 1944.

By the time that coastal units of the Royal Indian Navy finally landed at Akyab Island, on 3 January 1945 – possibly using landing craft disembarked at their base at Chittagong by Empire Elaine ten months earlier – the Japanese had melted away from the Mayu Peninsula, and the assault troops joined the rest of 14th Army under Slim on their relentless push towards Rangoon and victory in Burma. Whether Operation Bullfrog would have inflicted an earlier, decisive defeat on the Japanese, saving the thousands of lives lost at Imphal, Kohima and the other battles of 1944, or whether the landings would have exacted too high a price on the men and ships involved, can never be known.