The last certain photo of HMS Hood, taken from HMS Prince of Wales on the morning of 24 May 1941 shortly before Hood blew up and sank with all but three of her 1,418 crew (Imperial War Museum, HU S0190).

When the German battleship Bismarck put to sea on 19 May 1941 on her one and only offensive mission, ‘Operation Rheinubung’, she carried a boosted complement of sailors to provide prize crews for the many Allied merchant ships she was expected to capture. The naval action that followed, the most momentous of the war against Nazi Germany, is remembered for the relentless determination of the Royal Navy to pursue and sink Bismarck at whatever cost, spurred by the desire to revenge the sinking of HMS Hood in the Denmark Strait on 24 May. The drama and horror of those eight days – the sinking of the pride of the Royal Navy with all but three her 1,418 crew, and then the final destruction of Bismarck with even greater loss of life - overshadows the fact that Bismarck and her escort Prinz Eugen had left port not to engage the Royal Navy, but to wreak havoc among Allied merchant shipping in the North Atlantic. On the day of her departure there were eleven convoys at sea with striking distance, comprising hundreds of merchant vessels as well as troopships carrying Canadian soldiers to Britain. Had Bismarck been able to get among a single one of those convoys, her eight 15-inch guns could have wrought destruction far worse than the most devastating U-boat attacks. Revenge for Hood may have hardened the resolve of the Royal Navy, but behind the pursuit lay a fear among British commanders of a calamitous loss of foodstuffs, military supplies and troops at a time when the course of the war lay very much in the balance.

Like many of my generation fascinated by naval history I grew up haunted by the sinking of Hood, a feeling reawakened when her wreck was discovered in 2001 off Greenland and the first ghostly images were shown of her twisted remains, and of sailors’ boots lying among debris on the seafloor almost 3,000 metres deep. I was fascinated too because my grandfather was one of the many merchant seamen on the Atlantic during those months when Bismarck was such a threat; he had returned to the UK as Second Officer of the cargo ship SS Clan Murdoch in March 1941 and set off again in SS Clan Macnair in June, just after she had returned with convoy SL-74 from Freetown in West Africa. SL-74 had been the closest convoy to the Bismarck at the time of her sinking, and it was the convoy’s main escort, the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire, that delivered the torpedo attack widely regarded as the coup de grace that finished the Bismarck.

While I was in the UK National Archives researching my grandfather’s subsequent ship, Empire Elaine (see here), I discovered that the convoy record for SL-74 (ADM 237/1187) survives intact, including the convoy commodore’s report, his narrative and the decrypted cypher messages sent to the convoy during its passage. The documents reproduced below have never previously been published, to my knowledge, and provide a fascinating addendum to the mass of documentary material in the National Archives on the sinking of Hood and Bismarck and the aftermath.

The Ship Movement Card for Clan Macnair showing her departure from Freetown on 10 May 1941 in convoy SL-74 (an unusual detail, as the cards rarely identify convoys) (UK National Archives).

Clan Macnair, a 6,078 ton general cargo ship built in 1921, was on the last leg of a voyage that had taken her to India and South Africa; she left Freetown in on 10 May 1941 as one of 43 merchant ships forming convoy SL (Sierra Leone) 78, bound for Oban in Scotland. The convoy had only two escorts, HMS Bulolo, an Armed Merchant Cruiser, and HMS Dorsetshire, a heavy cruiser with a crew of more than 650. New of the loss of Hood left the crew of Dorsetshire ‘devastated’ and filled with ‘remorseless determination to get revenge’ (quotes from crew in Iain Ballintine, Killing the Bismarck, 2014, p 131). The loss of life was so great that many seamen, both Royal Navy and merchant, knew people on Hood; in my grandfather’s case it was one of his classmates from 1923-5 on the training ship HMS Conway, Edward Lewis, who had opted for Royal rather than Merchant Navy service and was a Lieutenant on Hood at the time of her sinking. After contact had been lost with Bismarck, there must have been considerable apprehension in convoy SL-74 that Bismarck’s likely course, south-east across the Atlantic, would cross their own, at a point that would turn out not far to the west of Bismarck’s final position some two hundred miles north-west of Cape Finisterre in Spain.

The 'Short Narrative' of convoy SL-74 by the convoy commodore, Commodore Brook, R.N.R., including mention of the departure of Dorsetshire and then her part in the sinking of Bismarck, May 26-7 (UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187)..

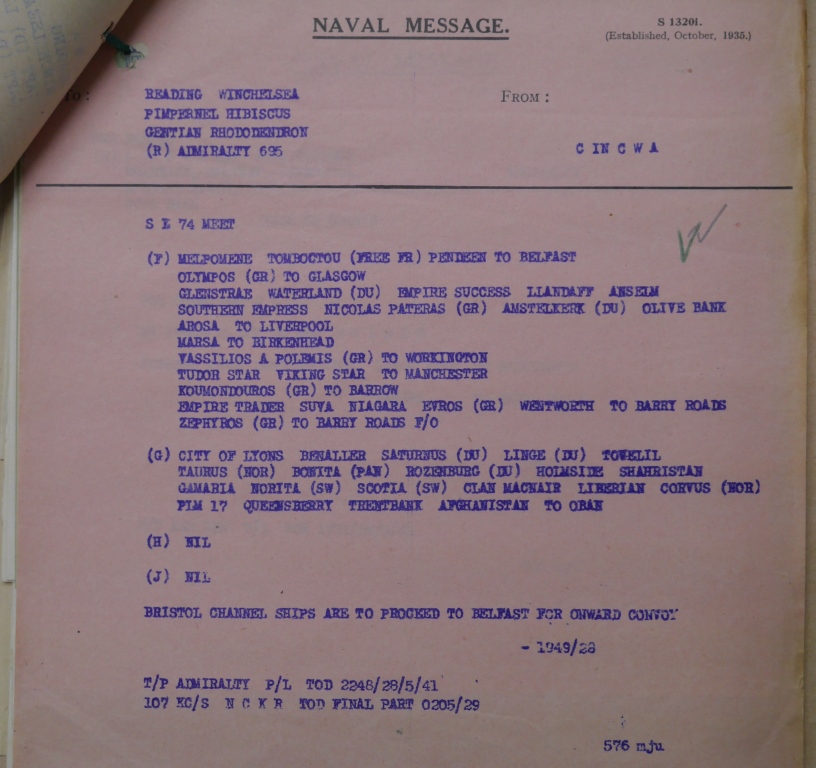

The final message in the record for SL-74 showing the convoy split as it approached the UK, with the second group, including Clan Macnair, destined for Oban (UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187).

At 1035 on 26 May an RAF Catalina flying boat signalled the position of a mystery ship that could only be the Bismarck, some 700 miles west-northwest of Brest and heading south-east towards Cape Finisterre. 25 minutes later the report reached convoy SL-74, at that point some 600 miles west of Cape Finisterre and 300 miles south of Bismarck’s reported position. Mindful of the possibility that the pursuing British capital ships might be too far behind and that Bismarck might reach a German-held port in the Bay of Biscay, Captain Martin of Dorsetshire decided to leave the convoy and sail north-east on a converging course with Bismarck. He would have known that Dorsetshire with her 8-inch guns would have been overwhelmed by Bismarck, but he would have hoped that she might inflict enough damage to slow Bismarck down in time for the other ships to arrive. In the event, the main British force did, of course, catch up with Bismarck, though it was Dorsetshire’s torpedoes that delivered the final blow. Meanwhile, convoy SL-74 escorted only by Bulolo crossed over the wake of Bismarck less than a day after she had passed that point, the convoy’s position on the following day being pinpointed by the cypher message reproduced below ordering a course change to avoid U-boat attack.

HMS Dorsetshire before the war (Imperial War Museum, Q 65701).

The actions of Captain Martin of Dorsetshire have come under much scrutiny, for two main reasons. The first was his decision to leave convoy SL-74 on the morning of 26 May and join in the pursuit of the Bismarck. He had not been ordered to do so, and by departing he left the convoy virtually undefended. His decision was unquestionably a huge risk to his own career, with the certainty of court-martial had any one of those ships in the convoy been lost or damaged by enemy attack. However, there is no hint of censure for his action by the convoy commodore, and instead one can detect a sense of satisfaction in the commodore's note on the following day that news had been received of Bismarck’s destruction by Dorsetshire herself, thus associating the convoy with this momentous event.

The last known photograph of Bismarck, shells falling around her and trailing smoke, taken from the railing of a British ship on 27 May 1941 (Lt J.H. Smith, RN, IWM A 4386).

In fact, even when Dorsetshire had been present, the convoy had been poorly defended, the heavy cruiser being less able to pursue and depth-charge U-boats than the corvettes and destroyers that escorted the north Atlantic convoys. The inadequate defence of the West African convoys was a constant issue through the war. After Clan Macpherson was sunk in May 1943 in Convoy TS-37, for which the escort was only one corvette and three armed trawlers, her Master, Captain Edward Gough, made an official complaint about the weakness and slow speed of the escorts as well as the lack of air cover. The Director of the Trade Division in the Admiralty replied that ‘The U-boat threat … off the West African coast is but a fraction of that in the North Atlantic and we obviously must allocate our limited resources in escort vessels accordingly. Were it possible, there is nothing we would like better than to give every convoy a really strong escort’ (quoted by Gordon Holman in the official history of the Clan Line during the war, In Danger’s Hour, Hodder and Stoughton 1948, p 134). This would have been little consolation for the survivor of a convoy which had been hit so hard - Clan Macpherson was one of seven ships sunk from TS-37 by a single U-boat, U-515, over the space of two days.

The second criticism of Captain Martin of Dorsetshire concerns his decision to break off the rescue of Bismarck survivors because of a perceived U-boat threat in the area of the sinking. By leaving convoy SL-74 the day before to intercept Bismarck and be in at the kill he had also committed his crew to one of the horrors of naval warfare, of having to abandon fellow mariners – albeit the enemy – to certain death in the water. The strenuous attempts by Dorsetshire’s crew to rescue Bismarck survivors are well-known, as well as the uncertainty over the alleged U-boat sighting (see Ballintine’s Killing the Bismarck, referenced above, p 198-9).

Convoy SL-74, UK National Archives ADM 237/1187).

The cypher message reproduced here to Bulolo on the following day, 28 May, indicating the course change for convoy SL-74 ‘to avoid U-boat’, would appear to strengthen the evidence for a threat in the area. One U-boat, U-74, is known to have surfaced at the site of the sinking after the British warships had left, and picked up three remaining survivors. Either that or another U-boat in the vicinity could have made its way north-west in the hope of attacking the nearest convoy, SL-74, though in the event failing to make contact as a result of the convoy’s course being altered. Whatever the truth, the cypher message bolsters the case that Captain Martin of Dorsetshire had good grounds to leave when he did, however grim the consequences for those of Bismarck's crew still alive in the water.

Of the Royal Navy ships mentioned here, HMS Bulolo survived the war – she was again to escort one of my grandfather’s ships, Empire Elaine, in the Indian Ocean in 1944, before serving as Headquarters Ship off Gold Beach during the Normandy landings. However, both Prince of Wales and Dorsetshire were to be sunk in separate incidents by Japanese aircraft within a year of the Bismarck action, with the loss of more than 500 crew between them. Of the merchant ships in convoy SL-74, seventeen were to be lost to U-boats by the end of the war. Of the many ships sunk in subsequent SL convoys, one of the worst hit was SL-78, only a month after the Bismarck action, when 8 ships of the convoy were sunk within the space of two days by U-boats off west Africa, similar to the losses two years later noted above in convoy TS-37 off the same stretch of coast. Soon afterwards in July 1941 my grandfather was in Clan Macnair plying the same waters south, in a convoy that by chance failed to attract the attention of the same U-boat pack.

Convoy SL-74, UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187).

The most poignant of the communiques in the convoy dossier for SL-74 is the message of congratulations from the Admiralty to the convoy commodore for bring all of his ships in safely. The survival of the men in that convoy was due to luck, to the reduced U-boat activity against convoys during Operation Rheinubung, and above all to the skill and tenacity of the Royal Navy sailors who fought and destroyed the Bismarck, including the 1,415 men who went down with HMS Hood.

Clan Macnair post-war, with her peacetime paint scheme and extended funnel. She was scrapped in 1952.