British army lancers - the regiment unidentified, but very possibly the 9th Lancers - on the move on a side track off the Albert-Amiens road, July 1916 (photo: Lt John Warwick Brooks, Imperial War Museum (IWM) Q 4054).

On 1 July 1916 the 9th Queen's Own Lancers, part of the 2nd Brigade of the 1st British Cavalry Division, were saddled up behind the front line south-west of the French town of Albert waiting for the breakthrough that was expected to follow the first hours of the British Somme offensive. All of the men had trained for up to five months at Tidworth and in the New Forest learning to use lance, sword and rifle from horseback, and for some the Battle of the Somme was the be their first experience of war. In the event, the breakthrough never happened and the first of July 1916 became the most calamitous single day in British military history, with almost 20,000 men killed – mainly from machine-gun fire – in those first few hours. Once the pattern of the battle was set, the men of the 1st Cavalry Division were ‘stood down’ and many of them used for other purposes. Their training and the continuing expectation that cavalry would win the war made them too valuable to be expended as assault troops, but as dismounted infantry and pioneers they dug trenches, manned sectors of the front line, helped to build narrow-gauge railways and cleared newly-won sectors of the battlefield.

Among the soldiers to join the regiment early that summer were my grandfather, Tom Harold Verrinder, and his older brother, Edgar Walter Rollings Verrinder. They had enlisted in the 12th Lancers in January 1916, been transferred to the 21st Lancers for the duration of their cavalry training and then been assigned to the 9th Lancers after their arrival at the Cavalry Depot in Rouen. My grandfather was immediately detailed to join a dismounted working party for the opening of the Somme campaign, and remained with them for five months in the battle area until rejoining the mounted regiment in November.

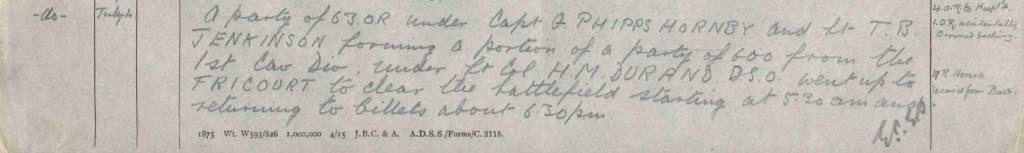

The 'dismounted party' in my grandfather's account of his war service - later that year to be formalised as the regimental Pioneer Company, part of the Divisional Pioneer Battalion - was one of several that summer organised at the Divisional and Brigade level, and included officers and men from all of the constituent cavalry regiments who might be assigned for a long period or relieved and replaced as circumstances dictated. Among other work, the grim task of battlefield clearance fell to the dismounted parties of the 1st Cavalry Division from early July. The participation of the 9th Lancers in this work can be reconstructed from the regimental War Diary , the War Diary of the Headquarters, 2nd Cavalry Brigade, and the regimental history, The Ninth Queen’s Royal Lancers, 1715-1936, by Major E.W. Sheppard (Gale and Polden, 1939), which contains eyewitness accounts not available elsewhere. The bodies of many of the infantrymen killed in the first waves of he offensive remained on the battlefield for days afterwards, and in the heat of that July the consequences can be imagined. On 4 July, the 9th Lancers party – ghoulishly called a ‘vulture party’ by one of the officers – moved forward to help clear the Fricourt area of the battlefield, where there had been over 8,000 British casualties. The entry below from the 9th Lancers War Diary shows that the party comprised two officers and 63 other ranks, part of a Divisional detail of 600 men, and was at work that day from dawn until early evening:

The 9th Lancers War Diary makes repeated reference to men being detailed to the Divisional working party, including two officers and 53 other ranks on 5 July, two officers and 67 other ranks sent near Fricourt on 24 July, one officer and 51 other ranks on 21 August and two officers and 51 other ranks on 8 October, with the 'regimental dismounted party' finally rejoining on 21 October - an event noted by Major Shepperd in the regimental history as the return of the vulture party', 'after their prolonged absence.' The larger constitution of these parties, including men from the other cavalry regiments in the Brigade (the 4th Dragoon Guards and the 18th Hussars), can be seen in the Brigade War Diary. The casualties suffered by the 9th Lancers during the five months of the battle were all among the dismounted parties, including 7 men wounded and one killed (Private W.R.W. Bell) on 30 July, five wounded and one died of wounds (Private C.H. Smart) on 2 August, and 7 wounded and one killed (Private Charles Edward Ridges) on 15 September.

Fricourt, showing British troops clearing away the debris, July 1916 (photo: Royal Engineers No 1 Printing Company, IWM Q 135).

One of the officers involved with dismounted parties from June to the end of the battle, 19-year old 2nd Lieutenant Martin Hunter, mentioned in the regimental Diary in July for returning with a dismounted party on the 5th and going out with another on 15th, wrote a personal diary - reproduced by Major Sheppard in his account of the Somme battle in the regimental history - that shows the dangers of working so close to the front line. The published account is undated, but the reference to six casualties means that it must refer to the few days surrounding the time when Private Smart was fatally wounded, noted above, on 2 August:

It is by no means an easy party we have got on. We had quite a merry night. Old Fritz would not leave us alone; he kept on sending over ‘coal-boxes’ and high explosive and shrapnel all night. About the middle of the night we got tear gas and shells; you cannot imagine the row that goes on all the time.

Stayed up all night. Bosches sent over a lot of ‘coal-boxes’, 5.9’s and high explosives. Hell of a night, no cover in trenches, no rations, six casualties, one gassed.

Shelled most of the night, and gas-attack.

Things got a bit too hot; one 5.9 landed about twenty yards from us and covered us all with mud, so we moved into dugout. Rats awful.

The Brigade War Diary contains the following letter of appreciation on 31 July to the 1st Cavalry Division dismounted party from the Commander of the 3rd (infantry) Division, which had sustained over 6,000 casualties from 11-27 July, and is a reminder that 'battlefield clearance' involved removing the carnage and debris not just of 1 July but also of the British assaults over the days and weeks that followed, in which the casualties soon exceeded the tally of that first day:

'Salvage collected after the advance', Morval, September 1916. These British Lee-Enfield rifles taken from dead and wounded men would have been among the material 'forwarded to the various dumps' noted in the letter above (photo: Lt John Warwick Brooke, IWM Q 4317).

The renewed British infantry attack on 14 July that included the 3rd Division saw the mounted troops of the 9th Lancers once again poised for cavalry action, waiting south-west of Albert. Elements of the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division ‘got into the retreating Germans with the lance’ at High Wood, but the opportunity passed and the 9th Lancers were again stood down, leaving a ‘vulture party’ still at work in the Fricourt area. During the final British offensive of the battle on 14 September the mounted regiment was again stood-to close behind the front line in the Carnoy valley where the first British tanks went into action, an event witnessed by my grandfather and also described in the regimental history.

Although the 9th Lancers were not to experience mounted action on the Somme in 1916, it was in the same area almost two years later that they were to see their biggest single engagement of the war, fighting a rearguard action during the German Spring offensive that cost the regiment 159 casualties – one of them Lieutenant Martin Hunter, who died of wounds on 11 April 1918. The fighting that my grandfather experienced then, as well as at Arras, Ypres and Cambrai in 1917, was more extensive than any action the regiment saw on the Somme in 1916, but there can be no doubt that for the men fresh to the front that summer – when my grandfather was only 19, the same age as Lieutenant Hunter – the experience of joining a ‘vulture party’ would have been a sickening introduction to the realities of war.

These two photos (click to enlarge) from the Imperial War Museum collection, the same source as the other two photos above, show, to the left, British cavalrymen of one of the Lancers regiments resting in a field near Fricourt in September 1916, and, to the right, British cavalrymen of one of the Lancers regiments cleaning their lances near Amiens, 1916. There is a very good chance that these are the 9th Lancers (photos: Lt Ernest Brooks. IWM 1228 and 1289).