This blog contains a summary of the ancestry of Rebecca Brandon, also known as Rebecca de Daniel Brandon and Rebecca Rodrigues Brandão, who was born in London in 1783 and died at Purnea near the Himalayan foothills in India in 1820. Rebecca was a Sephardic Jew from a family of merchants who had fled the Inquisition in Portugal in the mid-18th century. She was my four-times great grandmother, the wife of Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) John Littledale Gale of the East India Company’s Bengal Army. You can see her relationship to me here, through her great-granddaughter – my great-grandmother – Helen Mary Gale, who married Arthur Everett Gibbins. Despite the distance in time, the memory of Rebecca and her Jewish ancestry remained strong among her Gale descendants; my great-grandmother described her in notes she left for my father in 1964 as a ‘Portuguese Jewess who brought great beauty into the family at that period.’

Sephardic ancestry

The Bevis Marks Synagogue, built in 1701, was one of few buildings in the vicinity not to be damaged by bombing during the Second World War, and remains much as it would have appeared when Rebecca and her family formed part of the congregation in the late 18th century.

The Portuguese Jews of 18th century London, many of them wealthy merchants, had come to England as a result of the expulsion of the Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon in 1492 and from Portugal in 1496. Some had fled to England as early as the 16th century, but many, including Rebecca’s father Daniel, were more recent arrivals, the descendants of Jews who had remained in Portugal with their faith concealed but had been persecuted by the Inquisition. Their numbers in London rose from fewer than a thousand in 1700 to over twenty thousand a century later. Many including Rebecca's family settled in the eastern part of the old City north of the Tower of London, and were members of the Bevis Marks Synagogue. The London community formed part of the wider diaspora termed Sephardic after the Hebrew word Sepharad for the Iberian Peninsula, and differing from the Ashkenazi of central and east European descent who arrived in London in much larger numbers in the late 19th and early 20th century. Whether of Spanish or Portuguese descent, all Sephardic Jews would have traced their lineage back to the Israelites who had settled in Iberia in antiquity, in particular those who had fled following the Roman sack of Jerusalem and the creation of the province of Judea in the 1st century AD.

The decree expelling Jews from Portugal obliged those who wished to remain to reject their Jewish identity and adopt Christian practices and names. Many of these so-called ‘New’ Christians or conversos - among them Rebecca’s Brandão ancestors - secretly maintained their Jewish faith, and many of those were brought before the Portuguese Inquisition to test the truth of their conversion. A decree that should have resulted in Jews disappearing from the Portuguese records, their names henceforth indistinguishable from Christians, has in fact proved a boon for genealogists of Sephardic ancestry, as the proceedings or processo documents of the Inquisition that name the crime as ‘Judaism’ often give the full names of the accused, their age, the names of their parents and spouse, their town of origin and their occupation, as well as further details of their lives. Surnames that would otherwise show no indication of Jewish identity can thus be tied to converso families. Entire families could be brought before the Inquisition at one time, as in the case of Rebecca’s grandparents and their siblings, presenting a wealth of genealogical information. The online summaries of these records now available from the Portuguese National Archives can thus provide the information needed to reconstruct family relationships (see Sources, below).

A window in the 16th century Manueline style in the Jewish Quarter in Viseu. This style, incorporating marine elements and images of discoveries made by Vasco da Gama and the other early Portuguese explorers, is particularly interesting in this context given the maritime trade networks of Rebecca's great-grandfather Francisco and others of the Jewish community in Viseu at this period.

The processo documents show that Rebecca’s Brandão ancestors lived in Viseu, a town in north-central Portugal where buildings of the Jewish Quarter of the 16th century survive today. Rebecca’s father Daniel had been born in Viseu, and there were still Brandãos in Viseu during her lifetime. Although Rebecca’s direct line cannot be traced back with certainty before the mid-17th century, a search of the Portuguese archives reveals Brandãos in Viseu before that – including a merchant named João Brandão in 1515, and another Brandão in 1586 – and it is very possible that these were her ancestors too.

Members of Rebecca’s Brandão family who fled the Inquisition in the 17th and 18th century went to Bayonne in France and to Jamaica as well as to London, many of them flourishing as merchants. Those who remained in Portugal, including Rebecca’s great-grandfather Francisco, benefitted from the overseas trade networks thus created, and their resulting wealth was a further basis for persecution. By the second half of the 18th century few with the name Brandão remained in Viseu, where the Jewish community all but disappeared during the following century.

A note on names

The names used by Sephardic Jews present a particular challenge to genealogists. In common with most surnames of Sephardic Jews originating in Portugal, Brandão is a Portuguese, not a Jewish name; the Jews who remained in Portugal after 1496 also had to adopt Christian forenames to keep their Jewish identity concealed. Even after they had fled Portugal and could practice Judaism openly they usually retained their Portuguese surnames. Most of the Brandão family who settled in London anglicised their surname to Brandon, though the original Portuguese rendering remained in use among the Sephardic community, for example in the Bevis Marks Synagogue records. Children might be styled after their father’s name, so Rebecca Brandon is also recorded as Rebecca de Daniel Brandon as well as the original Portuguese Rebecca (or Ribca/Ribka) Rodrigues Brandão.

Most challenging for genealogists is the reversion to Jewish forenames of many of those who fled Portugal – thus João and Luisa Rodriguez Brandão, Rebecca’s grandparents, became Joshua and Esther, and João’s brother Lopo/Gaspar became Abraham. The reversion has the benefit that these individuals can now be identified as Jewish on tbe basis of their names alone; the problem lies in correlating those new forenames with the Christian names they had previously borne as conversos. Their identities can be revealed through discovering the same family relationships recorded for individuals with different forenames , for example in Rebecca’s great-uncle Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar’s Will (see below). A further problem is that the same few Jewish forenames are used repeatedly – names such as Abraham, Joshua, Raphael and Daniel for men, and Esther, Rebecca and Sarah for girls – and identical forename and surname combinations can appear among close relatives. To further complicate matters, it was common (as the Will of Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar shows) for first cousins bearing the same surname to marry.

Following common Iberian practice, the surname of a mother could be included and carried through the generations, as in the case of Rodrigues Brandão; a son might also take on his wife’s surname, such as Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar’s son Daniel Rodrigues Brandão, who is recorded after his marriage as Daniel Brandão Seixas - though not always (the fact that he was known by both names is noted in Abraham aka Lopos/Gaspar’s Will). In Portugal, a toponymic or nickname could also be added to the surname, for example the ‘Faro’ of Rebecca’s great-great grandfather Lopo Rodrigues Brandão Faro and his son Francisco Rodrigues Brandão Faro, referring to the port city in the Algarve where they carried out their overseas trade..

Sources

This letter of 1728 in the Portuguese Inquisition archives is from Rebecca's grandfather João Rodrigues Brandão, and would have been written shortly after his release.

The Bevis Marks Synagogue records include the births of Rebecca and her sister Sarah. Those records are not yet available online, but the volume containing the birth records can be seen at the British Library and elsewhere. For the lives of the Sephardic community in London in general, a wealth of detail on occupations and places of dwelling can be found in the trade and city directories, and in the many contemporary books, periodicals and newspapers now available online, with searches for names on Google Books, for example, revealing references that might never have been unearthed by conventional library research.

The two most important primary sources for this study have been the Wills in the UK National Archives and the Portuguese Inquisition documents in the Lisbon Instituto dos Arquivos Nacionais (formerly the Arquivo National da Torre do Tombo). The Wills, all downloadable, include those of Rebecca’s father Daniel and her grandfather Joshua aka João, and their respective brothers Raphael and Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar. These provide the names of wives, children, siblings and nephews and neices, and allow Rebecca’s immediate family to be reconstructed. The Inquisition processo files record the investigative phase of the tribunal, in which the denunciated individual – in these cases accused of Judaism, often with Heresy and Apostasy – was examined, including witness testimony. The processo documents for the Brandão family are particularly useful for revealing details of Rebecca’s great-grandfather Francisco, arrested along with his wife in 1698, and of eight of their children – including João and Lopo – who were brought before the Inquisition in 1724-5 (a useful pointer for me has been a list here by Arlindo N.M. Correia of the Brandão siblings, with references to their processo documents).

The availability of the Portuguese documents is a result of an initiative by the Portuguese government in 2007 to put as much as possible of the Inquisition archive online. One estimate is that the Inquisition tribunal at Coimbra, the nearest Inquisition court to Viseu, issued at least 9,547 sentences during its period of operation from 1541 to 1781, the majority of which were penances but including at least 331 burnings at the stake. The experience of the Brandão family was fairly typical, involving up to three years' imprisonment followed by an auto-da-fé, 'act of faith,' the ritual of public penance, after which they were released. The online catalogue entries for the processo documents do not include a full transcript of the proceedings but do provide the ages and the parents’ names, allowing all seven of Francisco’s sons and daughters to be identified as well as his parents, the earliest of Rebecca’s Brandão ancestors to be known for certain. Through mentioning their siblings in Visea and France, the Wills of Joshua and Abraham show that they are the same as the João and Lopos/Gaspar of the Inquisition records; Abraham, for example, leaves a bequest to the sons of his sister Isabel in France and another one to his sister Mariana in Viseu, the same as the Isabel and Mariana shown as sisters of João and Lopos in the Inquisition records.

The Jamaican connection

The early Jewish community in Jamaica had a colourful association with piracy, and one account by a family historian and Brandon descendant, Marilyn Delevante, suggests that Brandons were present at Port Royal in its heyday, before its destruction by earthquake in 1692. The earliest evidence for the name in Jamaica is the 1711 tombstone at Hunts Bay cemetery - near Port Royal - of Jacob Brandão, whom Delevante believes to have been born in Port Royal in 1665, the son of one Abraham Brandão of London, a Portuguese Jew. Whether or not these were originally Brandãos of Viseu, and related to Rebecca’s family, is unknown, though it seems likely. Rebecca’s first cousin Jacob Rodrigues Brandão, son of Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar, made out his Will in Kingston and instructed that he be buried there, so had evidently moved to Jamaica from London. Rebecca’s sister Sarah also moved to Jamaica, marrying Abraham Athias Silvera from another long-standing Jewish Jamaican family and having four children. One of Sarah and Abraham’s great-great grandsons is the Canadian architect Richard George Henriques – himself born in Jamaica – whose research on his family history in the Inquisition archives, published online in a series of articles in the Portuguese newspaper Terra Quente, has provided a valuable framework for reconstructing the early part of this genealogy and details of their lives.

Genealogy

My direct ancestors are in BOLD CAPITALS and their brothers and sisters are in bold lower-case, except where referred to again in the same paragraph or entry. Click on the words Will or processo for links to original documents or online catalogue entries.

Rebecca’s great-great grandfather,

LOPO RODRIGUES BRANDÃO (also known as Lopo Rodrigues Brandão Faro), married ISABEL RODRIGUES (also Isabel Rodrigues Portela), daughter of JOÃO RODRIGUES PORTELO, ‘mercador’, and GUIOMAR LOPES. Isabel’s processo shows that she was was from Viseu and was brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 14 April 1667, accused of Judaism, Heresy and Apostasy; she was released on 25 August 1670, when she was about 29 years old. Both parents are named in their son Francisco’s processo. The Arquivo Distrital de Viseu contains two deeds of Lopo Rodrigues Brandão, of 1662 and 1672, who may well be this Lopo.

Their son,

FRANCISCO RODRIGUES BRANDÃO FARO was brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra accused of Judaism, Heresy and Apostasy on 11 November 1698, underwent his auto-da-fé on 22 December 1701, and was released on 18 January 1702. His processo notes his home as Viseu, and as well as naming his parents names his wife, GUIOMAR RODRIGUES HENRIQUES, whose own processo - she was arrested on 31 December 1698, and released at the same time as him – shows that she was the daughter of FRANCISCO RODRIGUES PORTELA and LEONOR MENDES.

The buildings of the Portuguese Inquisition at Coimbra, where more than 9,500 Jews were tried for heresy between 1541 and 1781. The 'Patio of the Inquisition', the square to the right of centre, led to the tribunal chambers and cells in the buildings to the left. This was where most of Rebecca's ancestors who were brought before the Inquisition were tried and imprisoned, including her grandparents and great-grandparents.

Richard George Henriques’ research into the transcripts of these documents shows that Franscisco was a wealthy merchant of Viseu, born about 1662, with overseas business interests in Brazil, including the import of tobacco and sugar to Portugal and the export to Brazil of wine and spirits, fabrics and tools. His son Lopo (see below) is also described as an ‘estanqueiro do Tabaco’ in his own processo, and later as a tobacco broker in London. As well as houses in Viseu, Francisco owned a property in Lisbon with an atafona, a mill, that may have been used to grind tobacco, and was valued at 750,000 reals. Shortly before his arrest he sent 250 gold ducats to London, probably to keep some of his fortune out of the hands of the Inquisition. He died in Viseu on 29 October 1717, and was buried there in the Convent of S. Antonio dos Capuchos (now part of the main municipal park).

On his arrest in 1698 Francisco had five children, the eldest nine years old; a sixth, Matias, was born to his wife during their three years in prison at Coimbra, and more were born after their release. Of these, eight are known from their own processo documents, naming their parents and listing their home town as Viseu; they were all accused of Judaism and arrested by the Inquisition in late 1724 and early 1725, and released in late 1727. The ages of all but two, Lopo and Fernandez, are given in the online summaries of their processo documents; the ages of the others shown below are known from more detailed transcriptions of Inquisition documents researched by Richard George Henriques, as well as from the Wills of Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar and JOSHUA aka JOÃO.

The eight children known from their processo documents were:

Isabel Rodrigues Henriques (processo), who was brought before the Inquisition at Evora (the only one of the family not to have been tried at Coimbra) on 23 November 1724, when she was shown as married to João Dias Pereira. The processo summary has her age as 24, but Richard George Henriques lists her as the eldest daughter, born in 1689, and having married in 1707 to João Dias Pereira of Mirandela; they were spice merchants, and by 1724 had six children. Afterwards they moved to Bayonne, France; their sons, ‘residing in the Kingdom of France’, are included in the Will of their uncle Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar (see below).

Gaspar Rodriques Brandão (processo), born about 1691, a ‘mercador de Loja’ when he was brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 29 November 1724. He married Catherine Henriques Seixas, widow of Bernardo Lara Pimentel, and had five children; they were still living in Viseu in 1745. Carla Vieira, writing here (her note 71), presents a strong case for Gaspar being Abraham of the London Will, rather than his brother Lopo (see below).

JOÃO RODRIGUES BRANDÃO (processo), for whom see below.

Leonor Mendes Henriques (processo), born about 1700, brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 29 November 1724 and released in November 1727.

A cell in the Inquisition buildings at Coimbra, where members of the Brandão family were held for up to three years.

Mariana Henriques Portela (processo), born about 1704, brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 24 January 1725 and released in November 1727. She married Matthew Orobio Furtado; in 1745 they are recorded as having four children, all small. She is mentioned in the Will of her brother Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar as ‘residing in the Kingdom of Portugal’, suggesting that she was still living in Viseu in 1779, by which time she was a widow.

Mecia Henriques (processo), aged 17 at the time of her arrest and appearance before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 29 November 1724; she was released with her siblings in late 1727.

Fernando Rodrigues Portelo (processo), two years younger than Lopo, so born in 1704 or 1705, and described as an ‘estanqueiro’ of Porto when he was brought before the Inquisition on 24 October 1724 along with his brother Lopo.

Lopo Rodrigues Brandão (processo), born in Viseu on 18 April 1707. Some details of his early life are known from the research of Richard George Henriques. At the age of 14, his father having died, he was sent to the city of Porto, where his brother Fernando was already living. They were looked after by their kinsman Diogo Vaz Faro, a ‘grande mercador’, and they opened a tobacco business. In October 1724 Lopo was arrested by the Inquisition of Coimbra, and he was not released until May 1727.

At some point after that he fled to London, where ‘Abraham Rodrigues Brandão of Bevis Marks in the City of London, Merchant,’ made his Will in Portuguese on 25 January 1768, leaving bequests amounting to over two thousand pounds. The fact that this Abraham was one of the siblings of this generation is revealed by his reference in the Will to the families of his sisters Isabel in France and Mariana in Portugal. Richard George Henriques’ research suggested that Abraham was Lopo; another argument, by Carla Vieira and published here (her note 71), is that he was Gaspar.

Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar had at least six children, all mentioned in his Will: Anthony Lopes Seixas, deceased by 1768, who had married Abraham’s neice Guivinan Rodrigues Brandão, residing in Portugal; Daniel Rodrigues Brandão, also named (in a codical to the Will) as Daniel Rodrigues Brandão Seixas (granted denization at the same time as his cousin Raphael: see below); Salamon Rodrigues Brandão, married to Abraham’s neice Judith Rodrigues Brandão, residing in France; Moses Rodrigues Brandão, married to Abraham’s neice Hester Lopes Pereira, deceased by 1768, also living in France; Rebecca Rodriques Brandão; and Jacob Rodrigues Brandão, very probably the same Jacob Rodrigues Brandon whose Will was made in Kingston, Jamaica in 1776.

Returning to Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar’s older brother,

The signature of JOÃO RODRIGUES BRANDÃO from the 1728 letter in the Portuguese Inquisition archives shown above.

JOÃO RODRIGUES BRANDÃO (processo) was a ‘mercador’ and single when he was brought before the Inquisition at Coimbra on 25 January 1725. Like his siblings, he was imprisoned for almost three years, being released in December 1727. A letter in the Inquisition archive almost certainly of his, with his signature, is shown here. He was born in Viseu about 1700, and married LUISA MENDES SEIXAS, stepdaughter of his brother Gaspar (a daughter from Gaspar’s wife’s previous marriage). In 1745, they were living in Viseu, with five children - the oldest aged seven years - but by 1760 had fled to London, where they changed their names to JOSHUA and ESTHER (Ester).

His Will, made in London on 26 May 1779 (probated 1784) and translated from the Portuguese, shows that he was a ‘merchant of Mile End’. He instructed that he be interred in the new burying ground of the Portuguese Jews; his individual bequests amounted to more than three thousand pounds, and he left his household goods, plate, linen and jewels to his wife. The Will shows that they had at least six children; five had been born in Portugal between about 1738 and 1745, their order unknown but Daniel possibly being the fifth. Their names are styled as follows in the Will:

Sarah Brandão, a widow in her brother Raphael’s Will (see below). Sarah’s own Will, describing her as ‘widow residing at No 31 Tabernacle Row, City Road’ shows that as well as a son Joshua he had a daughter Esther, widow of Daniel Cohen D’Aroonda (?), to whom she left all of her furniture, plate, jewels and books. She named as executors her two nephews Joshua Brandon and David Brandon, presumably the sons of her brother Raphael. The Will, translated ‘from the Jewish language’, was proved on 2 August 1831.

Rebecca Barsilau, wife of Jacob Jesu(…) Barsilau.

Judita Brandão

A newspaper report of the denization on 13 May 1774 of Raphael Brandon and other Portuguese Jews, including his cousin Daniel Brandon Seixas.

Rafael Brandão, or Raphael Rodrigues Brandão or Raphael Brandon, whose Will was probated on 21 October 1821. The Will shows that he was a merchant of Haydon Square, London, and then of Leman Street, and was married to Sarah. The Will mentions their children Joshua and David Brandon, and his sister Sarah, by then a widow, as well as his brother Daniel; it also mentions his nephew Abraham Brandon and his niece Esther, widow of Daniel Cohen D’Aroondo. Esther was a daughter of his sister Sarah (see above).

Raphael is well-documented among London records of the period. He lived in the eastern part of the old City of London where many Sephardic Jews were based, first in Bury Street (Kent’s Directory of 1771 has him as a merchant of 14 Bury Street, St Mary Axe), close to the Bevis Marks Synagogue, and then at Haydon Square (from at least 1803 in his name alone, and then in 1814 as Raphael Brandon and Sons, merchants, at 6 Haydon Square, Minories), and finally at Leman Street further to the east. His denization record survives, showing that on 3 May 1774 ‘Raphael Brandon of Bury Street, merchant’, and ‘Daniel Brandon Seixas of Haydon Square in the Minories’ ‘took the Great Seal’, swearing their oath of allegiance to the Crown. Daniel Brandon Seixas was his cousin, son of his uncle Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar. Raphael had arrived with his parents from Portugal some time between 1745 and 1760, perhaps early on when he was a small child, and seeking denization would have reflected his commitment to remaining in England and his desire to own property.

Cruchley's map of 1827 showing the eastern part of the old City of London, with the Minories directly north of the Tower of London and Haydon Square leading off that to the right; Goodman's Fields lies just to the right of that, beyond the edge of the map. Raphael's earlier address, St Mary Axe, adjoins Bevis Marks near the top of the map. His brother Daniel's address at Tabernacle Walk lies to the north of that, beyond this map (see the second map below). Click to enlarge.

A particularly interesting legal document relates to an insurance policy made by Raphael Brandon at St Mary Bow, in the City of London, in February 1770, on goods to be transported on a ship called the Speedwell, bound from Newcastle to Bayonne; the insurer had renaged on the claim after the ship ‘ … on the high seas, by winds, storms and tempests, became and was wrecked, foundered, sunk, and wholly lost in the said seas, and the said goods and merchandises of the said Raphael were thereby then and there sunk in the seas and wholly lost, insured for one hundred pounds.’ Bayonne had been the home of his aunt Isabel and her husband João Dias Pereira, merchant, and presumably continued to be that of Isabel’s sons, ‘resident in the Kingdom of France’, mentioned in Raphael’s uncle Abraham aka Lopo/Gaspar’s Will; if so, this document may reveal the kind of family network that was a basis for much Sephardic mercantile activity at this period.

Raphael is probably the same Raphael Brandon who was President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews in 1812. He was one of the Jews belonging to the Spanish and Portuguese congregation in London who contributed to the City Patriotic Fund in 1803, in his case giving ten pounds. Along with Joshua, David (both very probably his sons) and Mrs Sarah Brandon, all of Haydon Square, he was a Governor (a benefactor) of the Asylum for the Support of the Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, in 1817. In his Will, as well as bequests to the Synagogue, the poor, his relatives and his servants, he left five thousand pounds (the equivalent of some half a million pounds today) to his wife Sarah as well as an allowance to her of one thousand pounds a year, and belongings including a carriage and horses and a stable house. The Death Duty Register for 1821, naming his wife Sarah, shows that his estate paid 1,037 pounds in that tax. In her own Will of 1826, Sarah left large bequests to her sons as well as numerous items of gold and jewellery to her grandchildren.

DANIEL BRANDÃO, for whom see below.

David Brandão. This David may be the David Brandon of Goodman’s Fields named as an executor in his brother DANIEL’s Will; however, Goodman’s Fields was the site of Leman Street, the final address of Daniel’s brother Raphael’s business with his sons, and as one of those sons was also called David he is possibly that one instead. As well as perhaps being the father of Abraham, recorded below as David's brother Daniel's business partner, this may also be the David Brandon noted in Hodson's Officers of the Bengal Army as the father of John Brandon, a Cadet of the East India Company's Army who arrived in India on 11 July 1806 and became a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Bengal Native Infantry. If this is so, it is conceivable that he sailed together with his cousin REBECCA, arriving Calcutta some seven months before her marriage to JOHN LITTLEDALE GALE (see below).

Returning to David and Raphael’s brother

DANIEL RODRIGUES BRANDÃO, later Daniel Brandon, was born in Viseu in Portugal in 1744 and died in London, leaving a Will (part of which is reproduced at the top of this blog), proved 2 May 1825, as well as a Probate Inventory. He is named in the Will as ‘of Tabernacle Walk, Finsbury Square, in the County of Middlesex, mustard manufacturer.’ Bailey’s Directory of 1781 lists his brother, Raphael Brandon, ‘merchant, of St Mary Axe’, along with ‘Joshua and Daniel Brandon, merchants, of Mile End.’ That Daniel may be the same, and Joshua his father, by then about 80 years old, who as we have seen is styled in his Will of 1779 as a merchant ‘of Mile End.’

From The London Gazette of 1793.

The first reference in Kent’s Directory to Daniel as a mustard manufacturer is in 1794, when ‘Brandon, D. and A.’, are listed as mustard-makers of Castle Street, City Road. By the time that directory had been published, his partner, Abraham Brandon, had gone bankrupt; the notice of the termination of their partnership can be seen opposite. It seems most likely that this Abraham was the nephew Abraham Brandon mentioned in Daniel’s brother Raphael’s Will, and perhaps therefore the son of their brother David. Though that partnership was never formally resumed, with Daniel appearing in the directories by himself as a mustard-maker of Castle Street, City Road, through to at least 1814, Abraham appears to have succeeded him in the business, as an Abraham Brandon, mustard-maker, of Castle Street, Tabernacle Walk, went bankrupt again – not once but twice, in 1828 and 1840 (the latter if not him then perhaps a son).

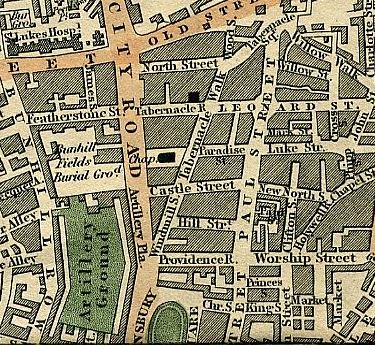

Cruchley's map of 1827 shows the precise location of Tabernacle Walk between Windmill Street and Tabernacle Square, as well as Castle Street at City Road. The addresses given indicate that Daniel's premises were at the junction of Castle Street and Tabernacle Row, where Windmill Street ends on this map. The entire stretch north of Finsbury Square was renamed Tabernacle Street in 1912. Click to enlarge.

Holden’s Directory of 1802 specifies Daniel’s address as 25 Tabernacle-walk, Finsbury. Tabernacle Walk at Castle Street can be seen on the 1837 map opposite; in 1912, Tabernacle Walk became part of the present Tabernacle Street, extending north-east from Finsbury Square. Many of the warehouses, manufactories and merchants’ premises along this street, an area of considerable Sephardic settlement, were extensively damaged by fire on 21 June 1891 and again during the Second World War, meaning that little survives today that would have been standing at the time when Daniel and his family lived there.

The three pictures below show buildings on Tabernacle Street that may have existed at the time of Daniel and his family. The first, an etching in the Illustrated London News of 30 June 1891 based on a photograph, shows the 'Great Fire in Tabernacle Street' during the night of 21 June, 'one of the most destructive fires in London of late years' in which nearly thirty establishments were damaged including 'large factories and warehouses of five or six floors, with their contents ... entirely burnt out.' The other two pictures show buildings that could be Georgian in date that survived that fire but were damaged when Tabernacle Street was hit by German bombs on the night of 11 January 1941 (click to enlarge).

DANIEL married LEA(H), and had two daughters:

Sarah de Daniel Brandon's son George Silvera of Jamaica (1808-84), from a photo of a painting reproduced here.

Sarah Rodriguez Brandão, also Sarah de Daniel Brandon, was born in London in 1782, and married at Bevis Marks in London on 2 December 1805 to Abraham Athias Benjamin Silvera of Kingston, Jamaica. She had five children, the second of them on the ship on the way to Jamaica, but she then appears to have separated from her husband –who died in Jamaica on 22 August 1842 – and returned to England, where she died on 13 May 1859, at The Green, Richmond, Surrey. The genealogy of her Jamaican descendants, including her son ‘Captain George’ Silvera and his large family, is extensively documented online, for example here.

REBECCA BRANDON, also REBECCA DE DANIEL BRANDON and REBECCA RODRIGUEZ BRANDÃO, was born in London in 1783. On 15 February 1807 in Calcutta she married Lieutenant JOHN LITTLEDALE GALE of the Bengal Army. He too had been born in 1783 in London, in Broad Street (St Peter le Poor), the son of JOHN GALE, a merchant originally from Whitehaven in Cumbria, and CATHERINE GALE née LITTLEDALE, who died a few days after his birth, aged only 22 or 23, and was also from a wealthy Whitehaven family. New Broad Street was about mid-way between Finsbury Square and Haydon Square, respectively Rebecca’s home and that of her uncle Raphael and his family, and it is conceivable that she had grown up knowing John and that they had planned to marry once he had become settled in India after his arrival there in December 1804.

Of the witnesses to Rebecca's marriage, Ann Bateman, presumably a friend of hers, married on 28 February that year also in Calcutta to Patrick Maitland, a partner in John Palmer and Co., Bankers of Calcutta, and grandson of the 6th Earl of Lauderdale. G.A. Simpson was also present at Ann Bateman's marriage. The other male witness we might expect to be a fellow-officer of John's, and indeed Hodson's Officers of the Bengal Army lists an Alexander Stewart of the Bengal Army who was a close contemporary of his, born in 1785, arriving in Calcutta in 1806 and serving in the 14th Bengal Native Infantry.

John Littledale Gale's Cadet Papers show that he had sailed to India on board the East Indiaman United Kingdom, leaving England on 10 July 1804 for a voyage of nearly five months to Calcutta. The ship taken by Rebecca is unknown, though it is possible that it was the same ship taken by John Brandon, arriving in India on 11 July 1806, if he is correctly identified as her cousin (see above, under Rebecca's uncle David Brandon). Voyages in the period following the Battle of Trafalgar, on 21 October 1805, were particularly hazardous because of the risk of French naval and privateer attack, with East Indiamen in convoys being involved in the Atlantic campaign of 1806 as well as action in the Indian Ocean, in addition to the routine risk of shipwreck- one East Indiaman departing England in 1806, the Skelton Castle, was never heard of again. Another East Indiaman loss, in February 1805 of the Earl of Abergavenney off Weymouth, had a family resonance for John Littledale Gale. His aunt, Ann Gale, had married Captain John Wordsworth Snr, master of the Earl of Abergavenney on several previous voyages, and it was his first cousin Captain John Wordsworth Jnr - brother of the poet William - who was master on her ill-fated final voyage, and went down with her along with 262 crew and passengers. Ann Wordsworth née Gale had signed her nephew John Littledale Gale's Cadet papers only a few months before his departure, and it was perhaps a matter of chance that neither he nor Rebecca embarked on the Earl of Abergavenney for their own voyages out to India.

Something of Rebecca’s life in India can be reconstructed from the military postings of her husband, listed in Hodson's Officers of the Bengal Army and Irving's Inscriptions on Christian Tombs or Monuments in the Punjab. John Littledale Gale was an officer in the 2/12 Bengal Native Infantry, and from 1807-8 was on active service with his battalion in the province of Oudh, participating in the storming and reduction of a number of forts held by refractory zamindars. Following several months’ leave in late 1809 he rejoined his battalion in February 1810 at Dinapur, and then proceeded with it in April 1811 to its new base at Barrackpur. In January 1812 he was appointed to temporary command of the Purneah Provincial Battalion, and in May of the following year he was given permanent command of the battalion, a position he held for the following eleven years. The battalion comprised some 860 sepoys with only two European officers – Gale and his adjutant – and was one of several ‘provincial’ battalions raised in 1803-4 to help police Bengal. Purneah (modern Purnia) lies close to the Nepal border, and during the Nepal War of 1814-16 the battalion was deployed to counter any infiltration by Nepalese forces into India; their routine work in detachments around the region included the suppression of thuggi and dacoits, ritual stranglers and brigands respectively.

This 1856 map of Bengal Presidency shows the geography of Rebecca's life in India, from her arrival and marriage in Calcutta in 1807 to her final seven years in Purneah, marked with the arrow. To the east is Burma, to the north Bhutan and Nepal and to the west the region of Oudh, where John Littledale Gale was on active service in 1807-8 while his regiment was based in Sitapur and then Lucknow. As the crow flies, the distance is about 850 km from Lucknow to Calcutta, about 450 km from Calcutta to Purneah and only about 60 km from Purnea to the Nepalese border. Click to enlarge.

Purneah was notoriously unhealthy, and Rebecca’s early death and that of three of her children is consistent with the high mortality rate from malaria in the district. From the time of the first European residents about 1770 the course of the local river gradually altered to produce much swampy land, ideal for the anopheles mosquito. The 1881 Imperial Gazetteer notes that ‘about 1820, the station became one of the most unhealthy in Bengal; and the old graveyard shows how great must have been the mortality among European residents.’ The ‘insalubrity that prevailed to so dreadful an extent’ , as the 1828 East Indian Gazetteer put it, had so deteriorated ‘that in 1815 the Bengal government considered a removal of the civil authorities to some other station unavoidable,’ an action that was finally taken in the 1830s when the European settlement was moved several miles from the original riverside settlement, resulting in a marked improvement in general health.

Despite this, the fertility of the land -caused in part by the prevalence of low-lying water that led to malaria - attracted European settlers who saw the potential, particularly for indigo plantation. The region to the west of Purneah was to be the home of many of Rebecca’s descendants over the next three generations, with her son JOHN GALE (1809-83) establishing himself there as an indigo planter in the 1840s and his grandsons continuing to live there until the 1920s; both my great-grandmother HELEN MARY GIBBINS née GALE (1881-1965) and her father Colonel WALTER ANDREW GALE (1855-1924), Rebecca’s grandson, were born on the family indigo estate near Tirhoot, not far from Rebecca’s grave in Purneah.

You can see Rebecca and John’s nine children in the chart below. She died on 6 August 1820, the Asiatic Journal recording 'At Purnea, Mrs Gale, the wife of Capt. J. Littledale Gale, most sincerely regretted, a kind and tender mother, and an affectionate wife.’ John remarried, in 1825, and had further children, but in his Will proved after his death at Simla in 1832 he remembered Rebecca, desiring 'that the jewels of my late wife Rebecca Gale be divided between my three daughters Caroline, Maria and Jane', all of whom had married Bengal Army officers. Rebecca’s tomb inscription, the the Old Protestant Cemetery, Purnea, is recorded in Howard and Crisps’ Genealogical Visitations and a List of Pre-Mutiny Inscriptions in Christian Burial Grounds, Patna Division:

The photos below show two descendants of DANIEL BRANDON whose appearance must reflects something of their Portuguese Jewish ancestry, and their descent from the two sisters - to the left, Sarah de Daniel Brandon's great-grandson Noel George Silvera (1886-1965), born in Jamaica, and to the right, his cousin and my great-great grandfather WALTER ANDREW GALE (1855-1924), born in India, grandson of Sarah's sister REBECCA DE DANIEL BRANDON.