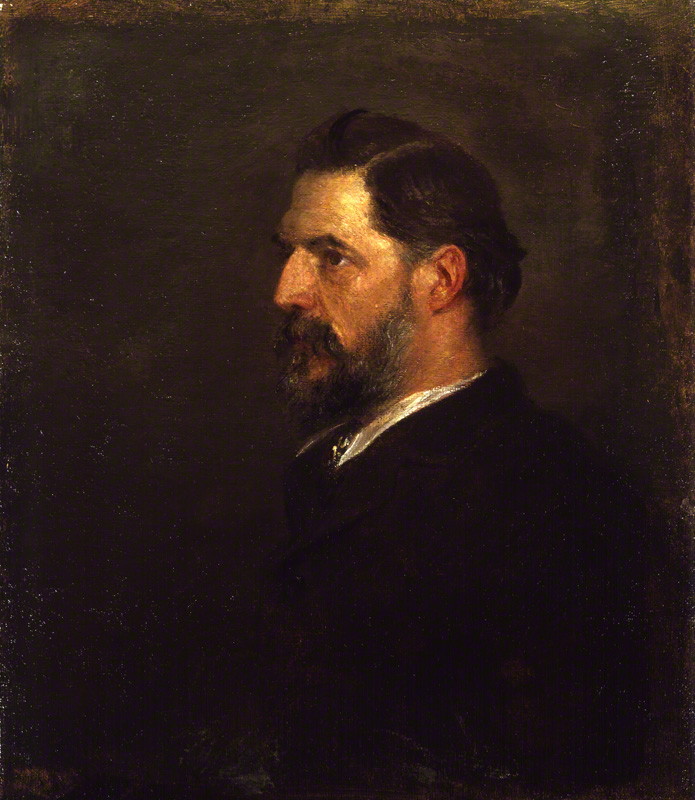

Flinders Petrie in 1900, soon after the discovery. Oil on canvas by George Frederick Watts. National Portrait Gallery, London, 3959.

My novel PYRAMID features the group of hieroglyphs shown above as an illustration dividing the Parts of the text. They’re not just decorative – they’re among the most famous hieroglyphs ever discovered in Egypt, a find that set the world alight at the very end of the Victorian era and gave scholars of the Old Testament something tangible to put alongside the Biblical narrative. In my novel, fictional Egyptologist Maurice Hiebermeyer discovers the hieroglyphs again in another context that makes their association with the Biblical Exodus indisputable, but the story of their real-life discovery almost 120 years ago is no less exciting and is one of the key moments of Egyptology, as significant for many as the discovery a generation later of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

In early 1896, the archaeologist Flinders Petrie – then only in his early 40s, but already acclaimed as one of the greatest Egyptologists – was directing excavations of a temple complex at Luxor, at the site of the ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes opposite the Valley of the Kings. Their discovery of the first known statue of Merenptah enabled Petrie to identify the building as the mortuary temple of the pharaoh, the late 13th century BC son and successor of Ramesses the Great. This in itself was of considerable interest, but neither the title of Petrie’s report, Six Temples at Thebes, nor his introductory chapter, give any hint of the excitement that was to follow. With typical archaeological understatement, all that he tells us by way of a preface was that most great discoveries are made by chance – requiring the archaeologist to excavate as completely as possible, not just to follow apparent clues – and that, in reflecting on the excavation, ‘though the results were less in some ways than I had hoped, yet in others they far exceeded what could have been expected.’

Petrie' original plan from his 1897 report Six Temples at Thebes showing the Temple of Merenptah at the bottom.

What they had discovered was an inscription that Petrie correctly predicted would be the most famous find of his career. The temple, constructed out of reused materials from the nearby temple of Amenhotep III, proved to have a pylon and colonnaded entrance fronting two courts, with chambers on either side. At the rear of the second court were parts of two colossal seated statues of Merenptah, one of them including the intact head - ‘The colour is still fresh upon it, yellow on the head-dress, red on the lips, white and black in the eyes.’

But the greatest find, in one corner of the forecourt, was a stele over ten feet high in the same black basalt as the statues, toppled forward from its original position against the wall. The rear face – the side facing upwards when it was excavated – contained an inscription of Amenhotep III, showing that it too had been reused from the temple of the pharaoh who had ruled some two centuries previously.

The photograph of the Merenptah Stele in Petrie's 1897 report, showing the difficulty of reading the hieroglyphs on the rough surface. Height: 3.2 m (currently in the Cairo Museum).

When Petrie was able to peer under it, he saw that the rough surface that had faced outwards on the courtyard wall - formerly the rear of the Amenhotep stele – had been carved with a detailed hieroglyphic inscription in which the name of Merenptah could be identified, below a coloured scene at the top showing Amen giving a sword to the pharaoh, backed by Mut and Khonsu. Petrie’s colleague and friend the German philologist Dr Wilhelm Spiegelberg was present that day, and was able to translate the largest part of the inscription as a celebration of Merenptah’s campaigns against the Libyans to the west. But when he reached the bottom lines he saw that they described a second campaign, against the ‘Sea Peoples’ to the north-east. His translation of that final part of the text is as follows:

‘(For) Ra has turned himself again to Egypt;

He is born to avenge it,

The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Banera

Meriamen, sun of Ra Merenptah-Hetephermaat.

The princes bend down, saying ‘Hail!’

Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows.

Devastated is Tehenu,

Kheta is quieted,

Seized is the Kanaan with every evil,

Led away is Askelon,

Taken is Gezer,

Yenoam is brought to nought,

The people of Israel is laid waste – their crops are not,

Khor (Palestine) has become as a widow for Egypt

All lands together – they are in peace,

Every one who roamed about

is punished by King Merenptah, gifted with life,

Like the sun every day.

It was Petrie who had first suggested over dinner that evening that the word I.si.ri.ar should be translated as ‘Israel’. ‘Won’t the reverends be pleased,’ he is said to have remarked. The find hit the headlines around the world, and to this day the Merenptah stele remains the sole reference from Egypt of the 2nd millennium BC widely believed by scholars to refer to the Israelites of the Old Testament.

You can see Petrie’s full original report, Six Temples at Thebes. 1896. With a chapter by William Spiegelberg, Ph.D., of Strassburg University (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1897), including all of the illustrations, by clicking here. The Wikipedia entry on the Stele of Merenptah discusses details of the inscription and the debate that exists among some scholars over the translation and interpretation. Both the statue of Merenptah and the Stele can be seen today in the Cairo Museum.

The final lines of the Merenptah inscription, showing the I.si.ri.ar hieroglyphs in the middle line just right of centre. It's a mirror image because this is a depiction from the 1897 report of the 'squeeze' taken by Petrie shortly after the stele was uncovered.